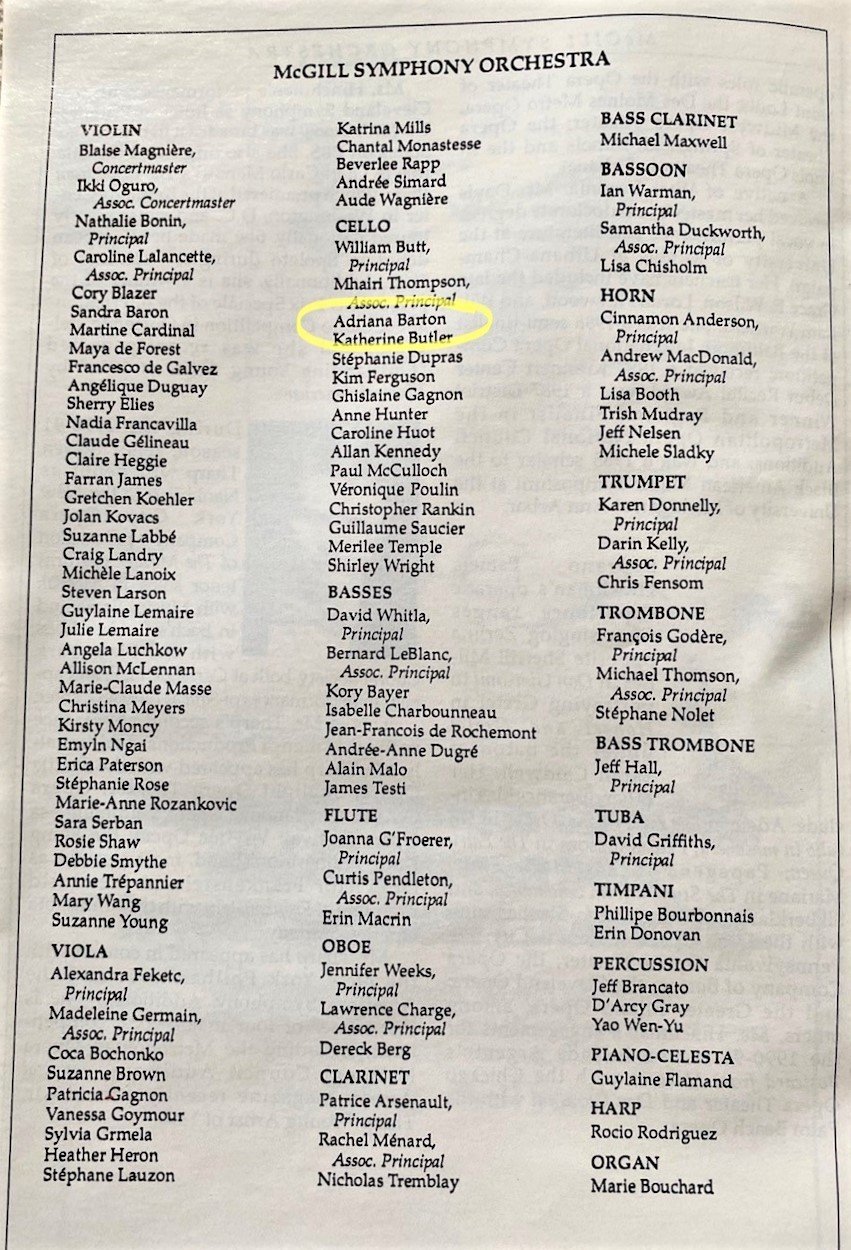

To celebrate the paperback release of my book Wired for Music, I am posting a series of photos, drawings and videos to illustrate key ideas in each chapter.

Sign up to receive an email alert for each new post. Enjoy!

A blurry Polaroid of me playing a plywood loaner cello about six months after I held the instrument for the first time. I was dutifully practicing in front of one of my mom’s paintings.

Prelude [excerpt]

I held a cello for the first time before a panel of stern-looking adults who peered down at me from a conference table, asking questions and taking notes. I was five years old — too young to realize this was an audition of sorts.

My mother, the artist Susan Feindel, was determined that my sister and I receive music training.

Mom was likely inspired by the months she’d spent sketching rehearsals of the National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa.

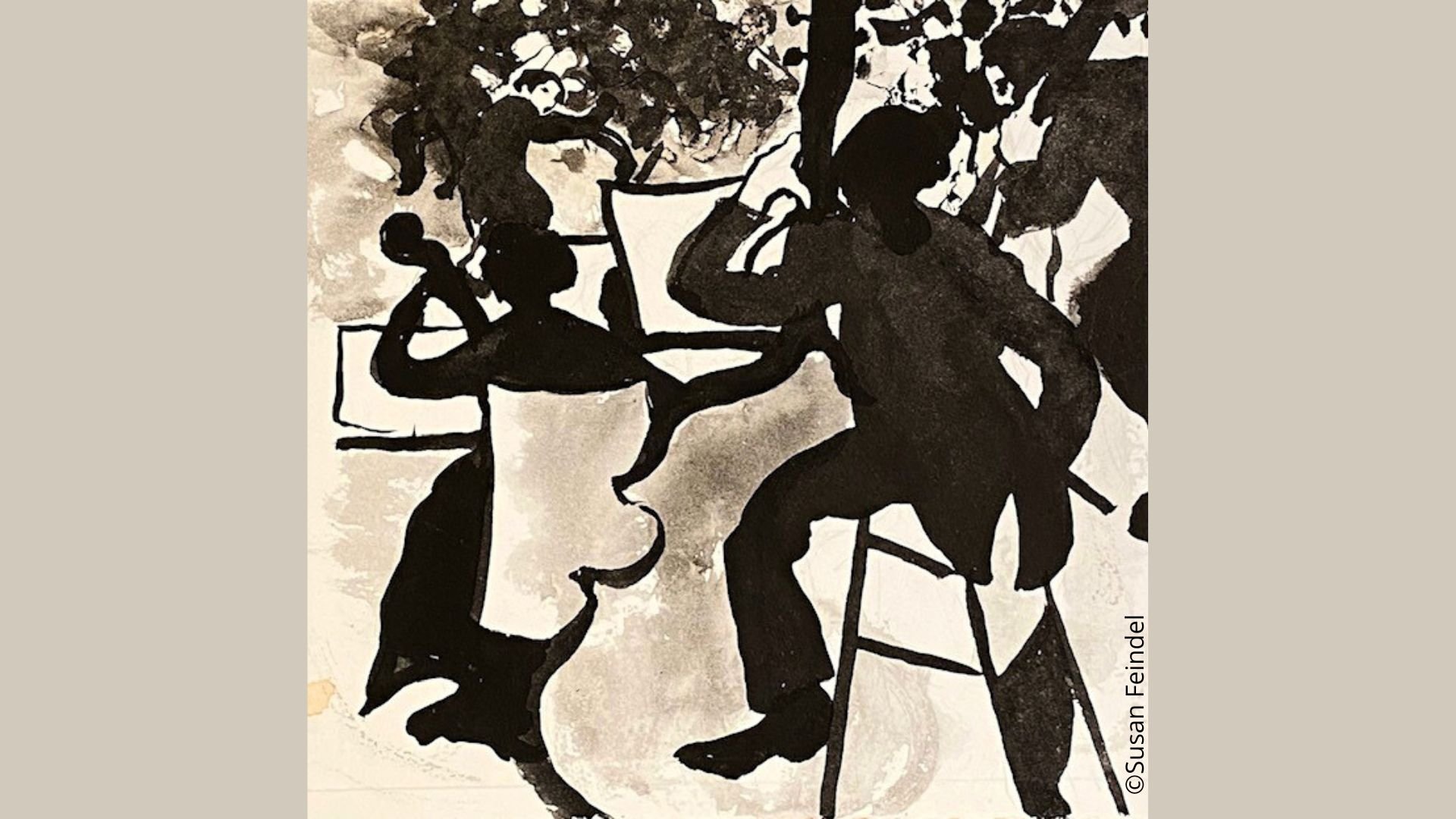

In her late 20s, while I was in nursery school, my mother spent her days drawing members of Canada’s National Arts Centre Orchestra. ©Susan Feindel. Reproduction in any form prohibited without written permission.

My mother’s drawings of orchestral musicians varied from extremely detailed to wildly abstract. ©Susan Feindel. Reproduction in any form prohibited without written permission.

Note the gestural conductor and intensity in the orchestra pit. ©Susan Feindel. Reproduction in any form prohibited without written permission.

Mom often sketched orchestral musicians from unusual angles to capture the physicality of their playing. ©Susan Feindel. Reproduction in any form prohibited without written permission.

In 1976 — a year after I began playing the cello — a selection of Mom’s musician drawings were exhibited at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa. (More than sixty of these drawings are now in the permanent archives of the NAC.)

With my mother’s unwavering encouragement, I went far with the cello. But years later, my adventures in music took me to places she never imagined…

Click here for the next chapter of Wired for Music: The Visual Companion. Sign up to receive an email alert for each new post.

To order the book Wired for Music, see links on this page.

Copyright note: The author is the copyright holder of all text but not all images included in this post. Every effort has been made to identify and indicate the copyright status of each image pictured. In some cases, copyrighted material has been included for the purposes of teaching and scholarship in accordance with “fair use” regulations in Section 107 of U.S. Copyright Law.

Please contact me with any questions, permissions requests, or concerns about copyright.