A chapter-by-chapter series of images illustrating key ideas in my book Wired for Music. Click here to view the series from the start.

Introduction [excerpts]

Riffling through my first homeowner’s insurance policy, I did the math: my most valuable possession was a cello I hadn’t played in years.

When I picked up the bow, a plume of white horsehair fell across my wrist. The wiry hairs had detached from the tip. My throat tightened. I had never seen my bow like this.

By my mid-30s, I hadn’t played my cello in a decade. Seeing my bow like this was a shock.

Some of us sing to Beyoncé when we’re going through a rough patch, or collect vintage synthesizers to play ’80s riffs from Duran Duran.

Collectors of vintage keyboards can get so into ‘80s synth sounds, they paint the walls to match!

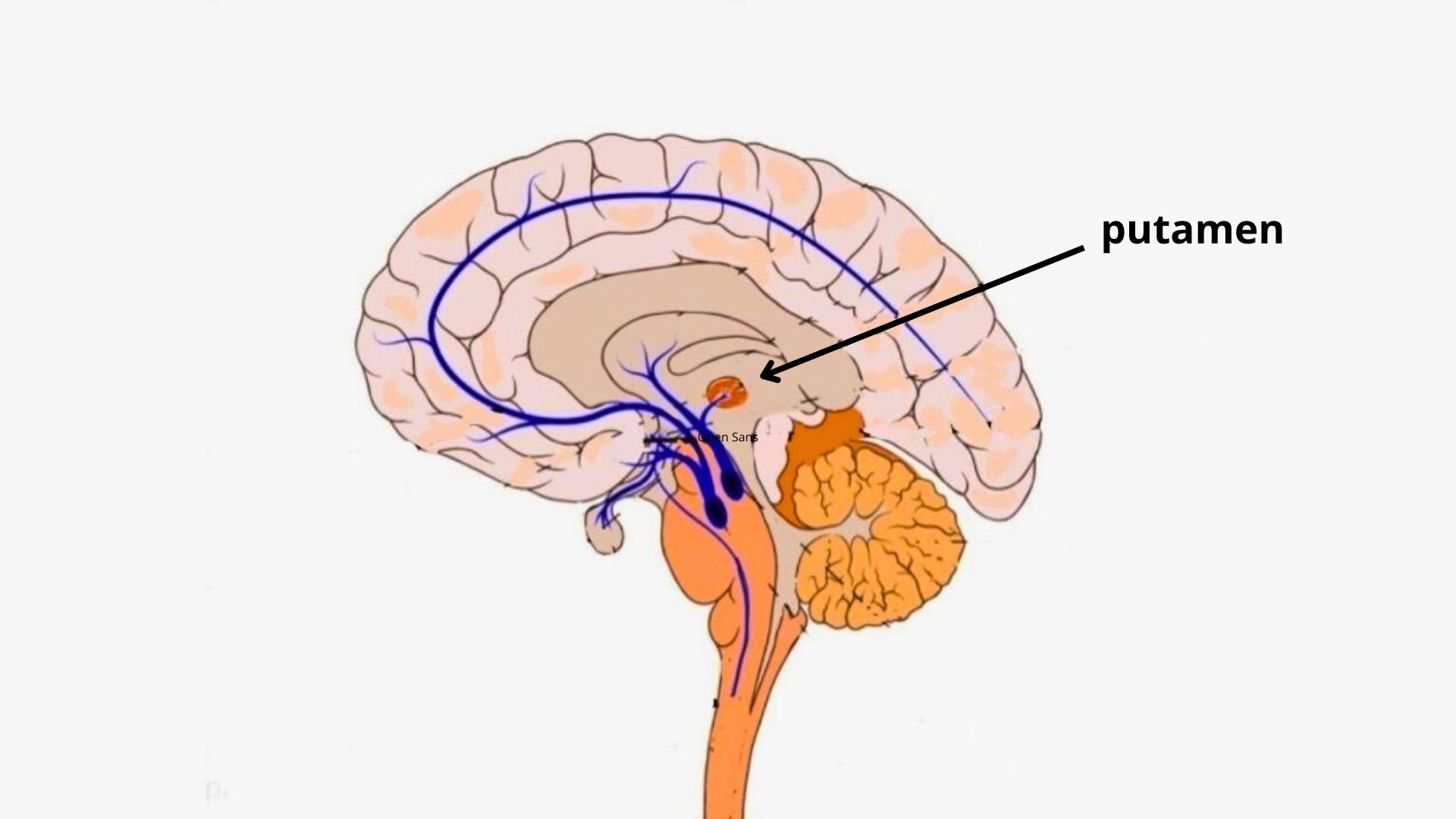

Even if we lie perfectly still, music fires up the putamen, a nut-shaped structure at the base of the forebrain that helps regulate our motor movements. When music tickles our eardrums, our gray matter shimmies back.

The nut-shaped putamen — a key structure involved in motor movement — is easily stimulated by music.

Before entering journalism, I spent seventeen years sawing away in a practice room, determined to become a professional cellist.

In university ensembles, I performed at Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto, the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, and once at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto, designed by the late Canadian architect Arthur Erickson. I remember being unnerved as spectators peered at the orchestra from the sides of the wraparound auditorium. Photo Creative Commons.

Canada’s National Arts Centre in Ottawa: What a thrill it was to perform in the same auditorium where I’d watched cellists Mischa Maisky and Yo-Yo Ma play.

Photo SamuelDuval, Creative Commons.

Carnegie Hall in New York City looks as magnificent today as it must have on opening night in 1891, when composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky conducted on stage. Photo Tdorante10, Creative Commons.

My break with the cello coincided with dramatic advances in neuroscience that began in the 1990s, which U.S. President George Bush proclaimed the “Decade of the Brain.”

Official logo created after President George Bush declared the ‘90s the “Decade of the Brain.” (Graphic design has come a long way since then!)

Image U.S. public domain.

In many ways, the flurry of new findings validated a belief long held by Indigenous peoples: music is a strong elixir.

In the lowlands of Siberia, Tuvan healers beat hand-held drums to make disease “fly away.”

Tuvan shamans drumming in the Second All-Russian Congress of Shamans, 2019, Tyva. Photo Irgit, Creative Commons.

In 1945, the U.S. War Department launched an ambitious music program for convalescing soldiers.

An Army Air Forces private, Harold Rhodes, invented a bell-toned therapy instrument using aluminum tubing from wrecked B-17 bombers.

Bedridden veterans learned to play his “xylette,” a lap-sized xylophone rigged to a piano keyboard.

Rhodes went on to found an electric piano company, and in 1971, the Fender Rhodes Piano Bass gave its signature sound to the keyboard riffs in The Doors’ hit “Riders on the Storm.”

Above: Army Air Forces private Harold Rhodes with an early prototype of his “xylette,” photo via Rhodes Super Site. Rhodes with metal tone bars, photo via World Piano News. Rhodes’ bedside “Pre-Piano” for convalescents, photo via Down The Rhodes. The Doors’ Ray Manzarek with a Rhodes Piano Bass in 1968, photo Creative Commons.

Decades later, universities worldwide began to rigorously test music’s capacity to heal.

Songs relieved pain in cancer patients. In surgical wards, music lowered anxiety as effectively as Valium.

Familiar tunes revived memories, pulling the elderly out of the fog of dementia.

Above: Watch the preview from Alive Inside, the 2014 documentary that drew broad attention to the benefits of music for people with dementia.

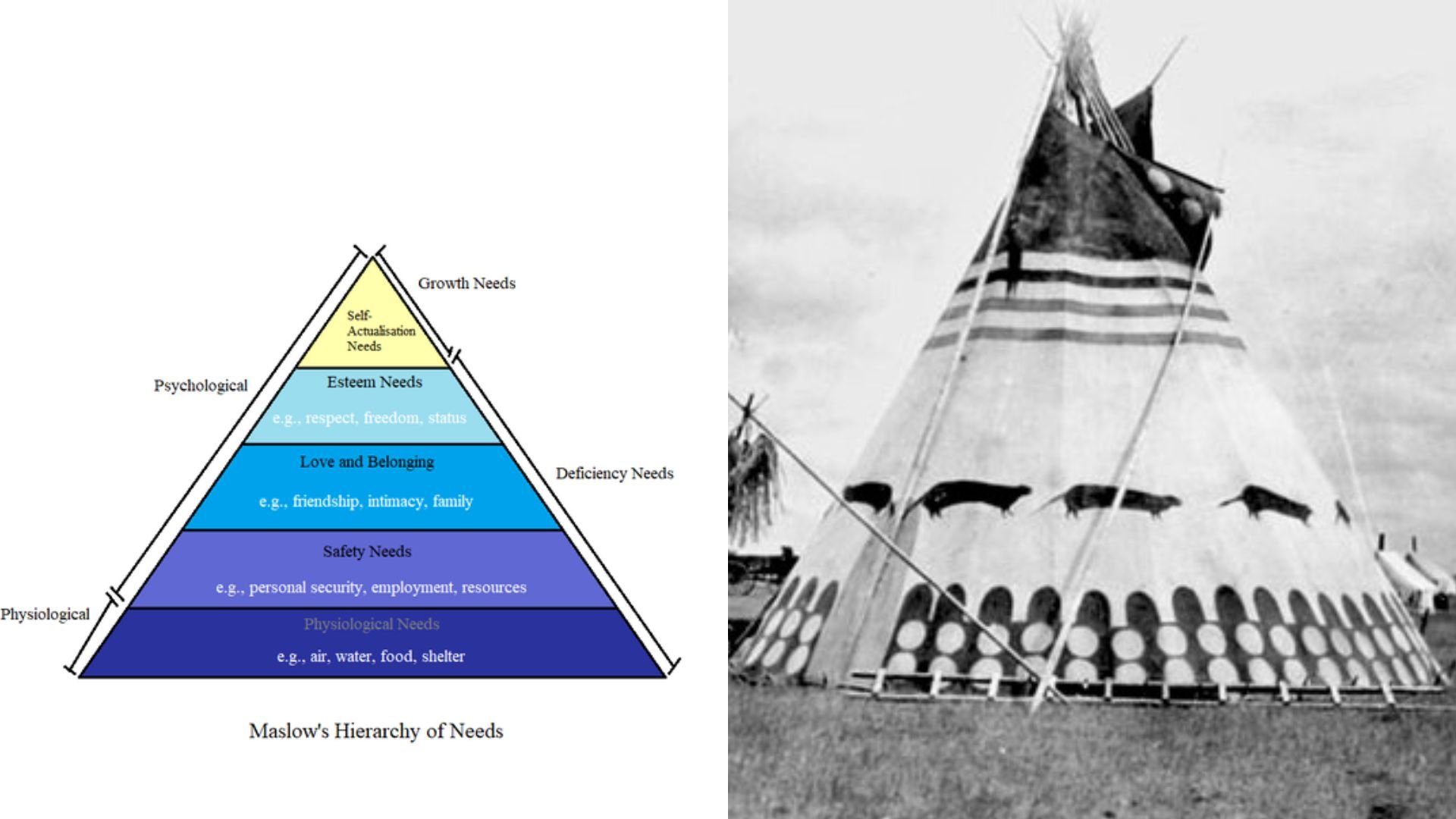

In organizing material for my book, I took cues from Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” (likely inspired, it turns out, by his experiences on a Blackfoot Reserve in the summer of 1938).

Left: Diagram of Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs,” Creative Commons. Right: Blackfoot teepee from 1880, photo in U.S. and Canadian public domain.

From a time before memory, our early ancestors pulled music out of wood, seeds, animal skin, bone.

Above: Rattles from Costa Rica (date unknown), photo public domain. Stringed musical instrument from ancient Egypt, photo Creative Commons. Prehistoric flutes and rattle made of wood and bone, photo Creative Commons.

Embedded in primeval rituals, and tucked inside our gray matter, are surprising answers to a simple question: How can music help us heal, and thrive?

Iron Age figurine playing a drum. Photo Israeli National Maritime Museum, Creative Commons.

Click here for the next chapter of Wired for Music: The Visual Companion. Sign up to receive an email alert for each post.

To order the book Wired for Music, see links on this page.

Sources for all statements in this post can be found in the endnotes of the hardcover and paperback editions.

Copyright note: The author is the copyright holder of all text but not all images included in this post. Every effort has been made to identify and indicate the copyright status of each image pictured. In some cases, copyrighted material has been included for the purposes of teaching and scholarship in accordance with “fair use” regulations in Section 107 of U.S. Copyright Law.

Please contact me with any questions, permissions requests, or concerns about copyright.

Disclaimer: Discussions about health topics provided in this post, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment. The author accepts no responsibility or liability for any health consequences relating to information published on this website.