A chapter-by-chapter series of photos, drawings and videos illustrating key ideas in my book Wired for Music. Click here to view the series from the start.

Chapter 1: Strings Attached [excerpts]

My cello has ribs of maple and a front of soft spruce, bonded together in Germany more than a century ago. Heavy and golden, it has many scars.

A previous owner must have dragged my century-old cello on hard surfaces, roughening the edges on both sides.

When I was twelve, my teacher instructed my mother to find me a proper cello, saying I could no longer develop my sound on one of the conservatory’s loaner models.

My mom, never flush, paid a visit to the Ottawa studio of a Slovak luthier, Joseph Kun.

My mother, the artist Susan Feindel, painted this watercolor of the late Ottawa-based luthier Joseph Kun — inventor of the “Kun” violin rest. His beautifully crafted cello and violin bows became collectors’ items after his death in 1996. ©Susan Feindel. Reproduction in any form prohibited without written permission.

On Tuesdays after school, I waited for my cello lesson in the drab government building that housed the Conservatoire de musique du Québec.

As a child, I spent three or four nights a week in the grim state-run conservatory (far left) on the campus of l’Université du Québec in Hull, across the river from Ottawa.

My teacher would pull apart the fingers of my left hand as far as they would go, forcing them to play whole tones on an instrument too big for my kindergarten hands.

To this day, although I stopped playing the cello three decades ago, the left pinkie on my fingering hand stretches a full inch farther than the right.

Sometimes my mom would sit in on my lessons and sketch.

In this drawing with my first cello teacher (left), I am about nine years old. I look solemn and melancholy in every sketch my mom did of me playing the cello. ©Susan Feindel. Reproduction in any form prohibited without written permission.

Mom would say she exaggerated my fingers to emphasize the powerful contortions at work, but I can hardly stand to look at this sketch. It makes playing the cello look painful and unnatural.

Left: Me at age 15, with ten years of cello under my belt. Right: In this sketch by my mom, I have no body, no heart — just contorted fingers and a look of intense concentration. ©Susan Feindel. Reproduction in any form prohibited without written permission.

For my sixteenth birthday, my mother took me to see Yo-Yo Ma perform Haydn’s Cello Concerto in D, a frothy yet technically demanding piece.

Backstage, my mom pulled out a copy of Ma’s latest album and told him I was studying the cello. He smiled at me and asked, “What are you playing?”

The Saint-Saëns concerto, I replied. On the album, he wrote in bold letters, ‘To Adriana Happy Birthday!!! + good wishes for S.S. etc. etc. YYM.’

But that wasn’t all. “Would you like to try my cello?” he asked.

I still have the vinyl album Yo-Yo Ma signed for me when I turned 16. He wrote: “To Adriana Happy Birthday!!! + good wishes for S.S. etc. etc. YYM.”

Leafing through The Strad [magazine] one day, I spotted a full-page ad for the Cleveland Institute of Music showing a man cradling his cello. He was Stephen Geber, principal cellist of the Cleveland Orchestra, routinely listed among the top orchestras in the world.

My mom drove me five hundred miles from Ottawa for my audition.

Home of the Cleveland Orchestra: Severance Hall. During my studies in Cleveland, I received regular free tickets to see this magnificent orchestra, led at the time by the brilliant conductor Christoph von Dohnányi. Photo Cbusram, Creative Commons.

At age 18, in my second year of university studies in Cleveland, I dressed as a “vampire victim” for Halloween. I smiled for the camera (left) but inside, my self-doubt as a musician was draining the life out of me.

I spent my first two years of university studying at the Cleveland Institute of Music, built in the late 1950s in University Circle, Cleveland, Ohio. Photo in public domain.

A marble-shaped cyst appeared in my right wrist, followed by another in the left. But I didn’t think to ask myself if my body was trying to tell me something.

Debilitating tendinitis came next.

A ganglion cyst: Mine were larger and in each wrist, erupting near the start of my freshman year as a scholarship student in Cleveland.

Photo GEMalone, Creative Commons.

After abandoning my studies in Cleveland, I decided I should at least finish my degree.

I phoned McGill University in Montreal and learned that the cellist Antonio Lysy, an international solo artist, was joining the faculty and looking for students. Three weeks before the start of the term I was offered a spot.

Montreal dazzled me with its Paris-in-North-America flair.

I lived for the high points, like the time my university orchestra [McGill] performed at Carnegie Hall in New York.

All through the dress rehearsal, I kept gawking at the elliptical ceiling and the gilded columns jutting from creamy walls.

“How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice.” Photo Wholtone, Creative Commons.

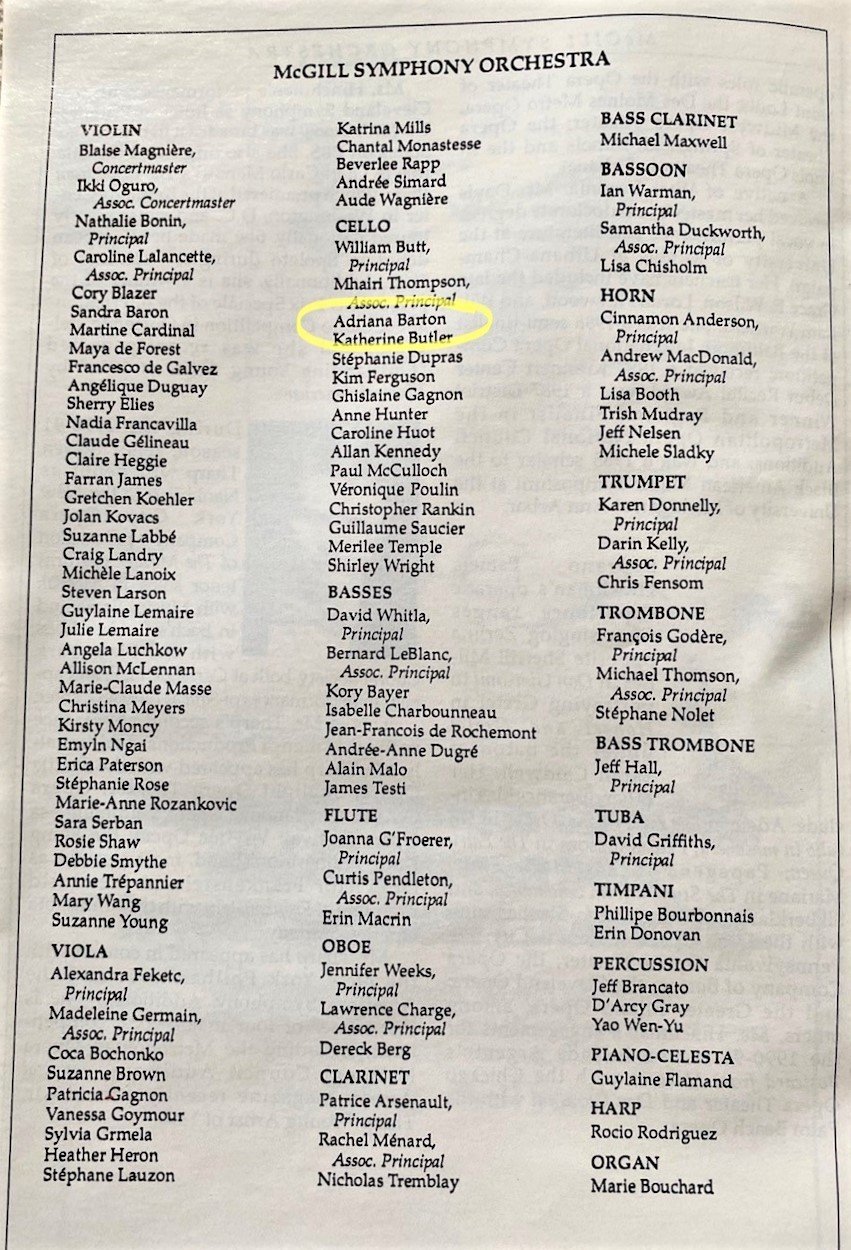

Playing Carnegie Hall was a peak moment. I still have the glossy program with my name printed inside.

Inside a chapel on a dark December afternoon, Montrealers had gathered to mark unthinkable loss.

Two years before, a misogynist gunman had opened fire at an engineering school across town. … I was twenty-one, sitting with my cello to the side of the crowd, waiting for the signal to play.

A contemplative event at Loyola Chapel on the Concordia University campus. In the same chapel, I performed solo Bach in a vigil to commemorate the victims of the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre. Photo via Hospitality Concordia fonds, Concordia University Records Management and Archives, Reference code I0042.

After the vigil, shaky and depressed, I found myself a therapist. She recommended a book, You Can Heal Your Life, by Louise Hay, an American cult figure who claimed to have cured her terminal cancer through loving affirmations and self-forgiveness.

I wrote page after page of lines like “I am a good person. I am a talented musician…”

Louise Hay’s book on positive affirmations was all the rage in the 1990s. But much as I tried, I couldn’t self-help my way out of cello-induced tendinitis and debilitating self-doubt.

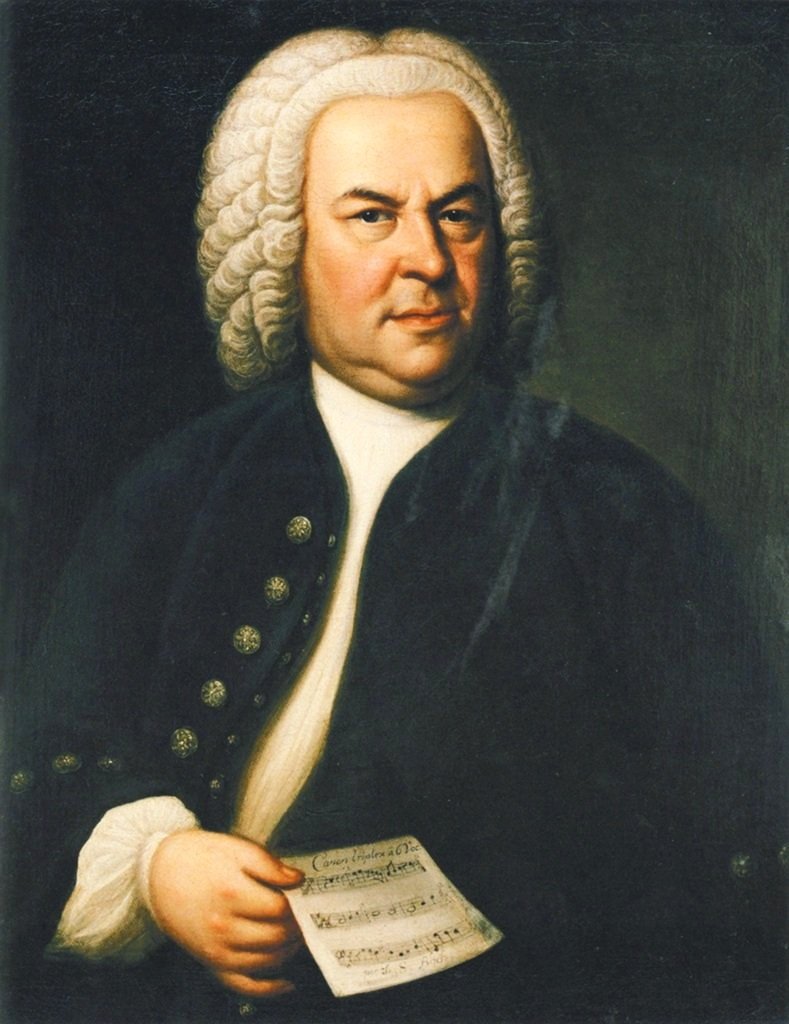

Many people describe music as a ‘universal language,’ a tuneful lingua franca. But this metaphor, penned in 1835 by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, assumes the same music speaks to us all.

The American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, circa 1850.

In his prose collection Outre-Mer: A Pilgrimage Beyond the Sea, published in the 1830s, Longfellow penned the phrase “Music is the universal language of mankind.” A romantic ideal turned cliché.

To the modern ear, this phrase has colonial undertones. Out of all the world’s music, which did he consider to be the “universal language”?

Photo in public domain.

I quit the cello after 17 years and took the only job I could find, as a receptionist at CHOM-FM radio station, “Montreal’s Home for Classic Rock.”

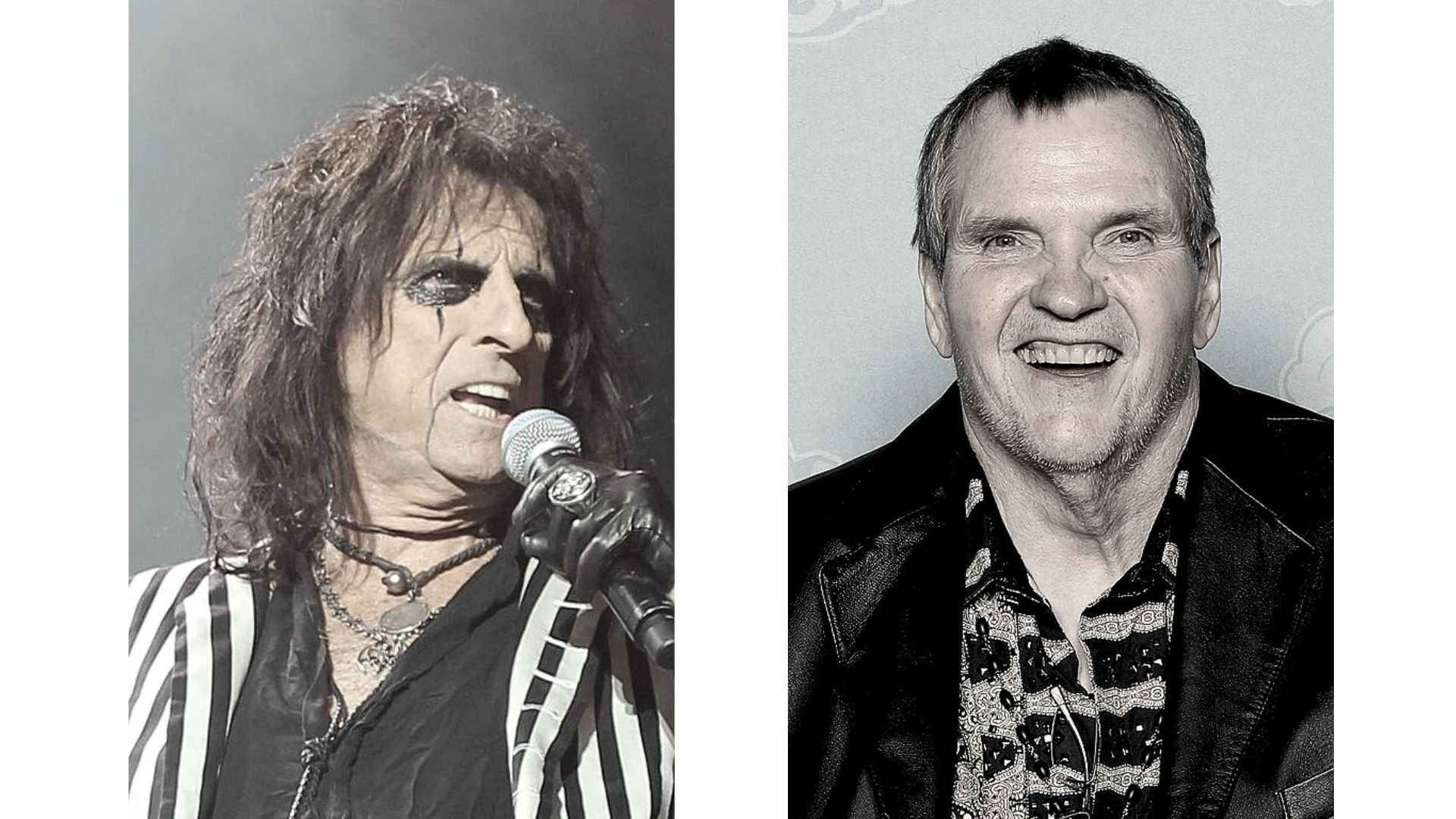

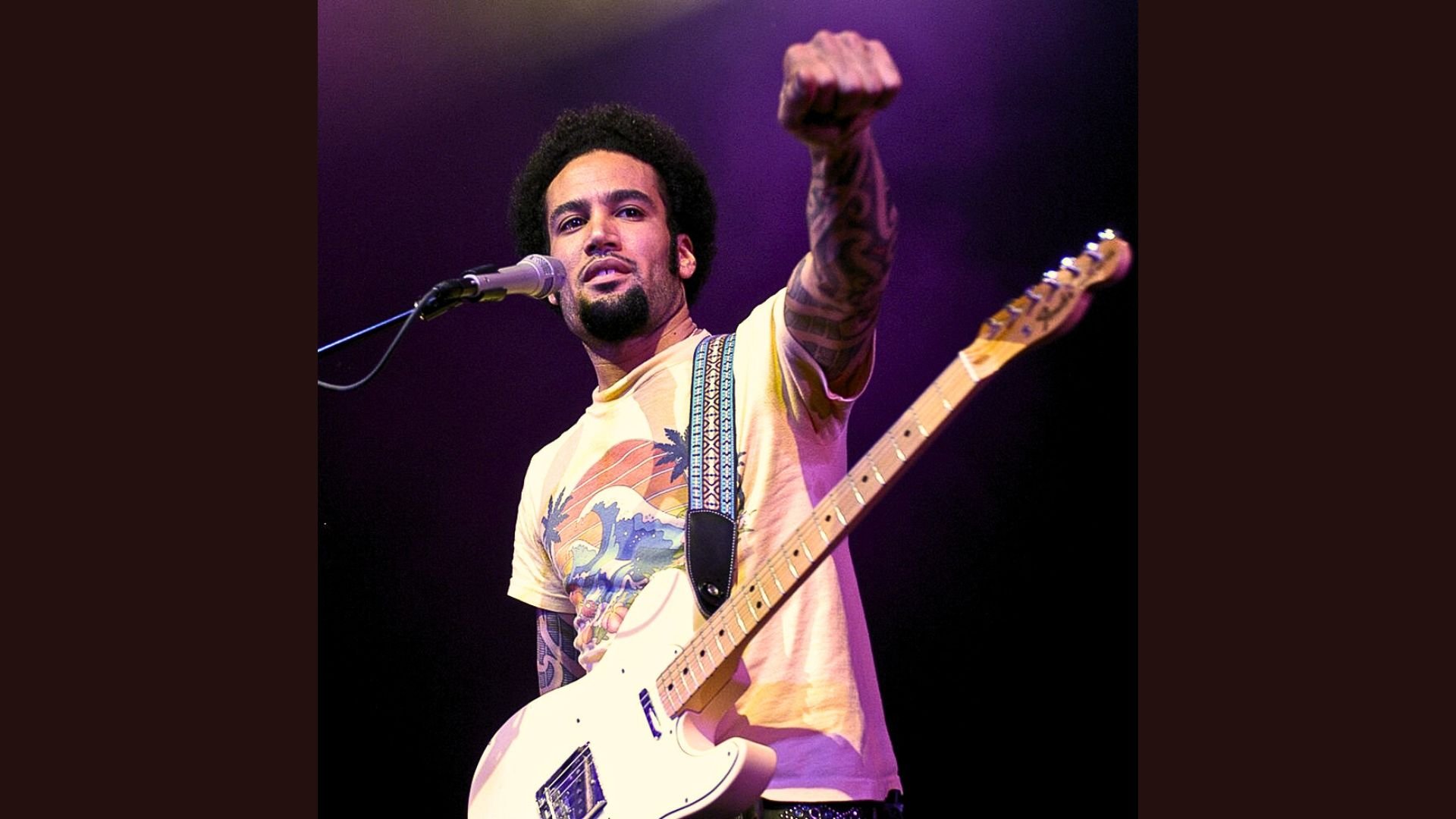

There I was, a classical-music geek, greeting rock stars I’d never heard of in the waiting area: Good afternoon, Alice Cooper. Hello, Meatloaf.

Two of the rocks stars I greeted as a radio-station receptionist. Left: Alice Cooper, photo Biha, Creative Commons. Right: the late Meatloaf, photo Super Festivals, Creative Commons.

Encountering so many different ways of making music gave rise to an unsettling thought: maybe, despite seventeen years of cello training, I had never really learned what music was all about.

Follow here to view future chapters of Wired for Music: The Visual Companion. Sign up to receive an email alert for each post.

To order the book Wired for Music, see links on this page.

Sources for all information in this post can be found in the endnotes of the hardcover and paperback editions.

Copyright note: The author is the copyright holder of all text but not all images included in this post. Every effort has been made to identify and indicate the copyright status of each image pictured. In some cases, copyrighted material has been included for the purposes of teaching and scholarship in accordance with “fair use” regulations in Section 107 of U.S. Copyright Law.

Please contact me with any questions, permissions requests, or concerns about copyright.

Disclaimer: Discussions about health topics provided in this post, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment. The author accepts no responsibility or liability for any health consequences relating to information published on this website.