A chapter-by-chapter series of images illustrating key ideas in my book Wired for Music. Click here to view the series from the start.

Chapter 4: Mood Music [excerpts]

One evening at an art gallery, I bumped into a journalist from Canada’s newspaper of record, The Globe and Mail.

The Toronto-based paper was looking for an editor to assign arts stories in Vancouver, she said. “You would be perfect for the job.”

I was hired within days. I could hardly believe my luck.

In my first two years at The Globe and Mail, I assigned and edited more than six hundred articles on visual arts, theatre, music and pop culture for a weekly arts and entertainment section in Vancouver, B.C. Photo Adriana Barton, all rights reserved.

As I scrolled through press releases, a jaw-dropping report about music caught my eye:

“Music releases mood-enhancing chemical in the brain.”

Huh. My classical training had left me anxious and depressed. The opposite effect. I wracked my brain thinking about how the new findings might have been true for me back then.

A devastating memory from my teen years came to mind. Flashing back to the anguish and its long aftermath, I realized for the first time that it was music that had helped me get through it.

The summer I turned fifteen, I loaded my cello onto a bus for a day’s journey from my hometown of Ottawa to a music academy in Charlevoix, Quebec.

I saw many familiar faces as I unpacked my things, but the bunk beds were filling up fast, with no sign of our principal violinist, Aruna, or her whiz-kid sister Rupa from the second violins.

“Didn’t you hear?” someone said. “They died in the Air India crash.”

Oh God.

On June 23, 1985, the bomb exploded while the passenger jet was in midair, sending the bodies of all 329 people — Aruna, Rupa, and their mother, Bhawani, too — hurtling into the Irish Sea.

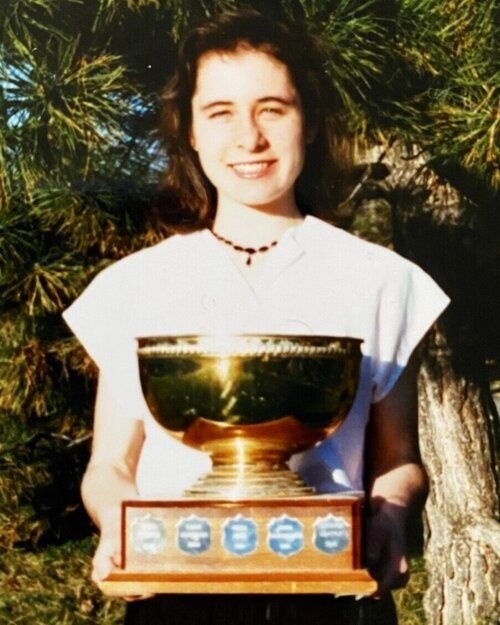

The following spring, at the Ottawa Music Festival, the judges declared me the winner of the trophy for strings. But where was the prize?

Unbeknownst to me, Aruna had won it the previous year. Wordlessly, her father presented me with the trophy. Then he gave me something else: a photo of Aruna holding the golden cup, radiant and beautiful, two months before she fell from the sky.

The Air India bombing was the biggest mass murder in Canada’s history. Yet despite knowing two of the victims, I don’t remember talking about it with anyone.

Instead, I spent my free time barricaded in my room, lonely and depressed. Whenever I had the house to myself, though, I’d lie on the couch listening to my idol, Jacqueline du Pré, playing Elgar’s haunting Cello Concerto in E Minor.

Over and over, I’d listen and weep.

Jacqueline du Pré wowed the world in 1962 with her gut-wrenching interpretation of Sr. Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E Minor. When multiple sclerosis forced her to stop performing at age 28, this haunting concerto became the anthem of her tormented life.

People struggling with depression often gravitate to melancholy music. And it turns out we have healthy reasons for choosing sad songs when we’re down.

Jonathan Rottenberg, director of the mood and emotion laboratory at the University of South Florida, and a graduate student, Sunkyung Yoon, conducted a study using music rated by Western listeners as neutral, happy, or sad.

Overall, people with clinical depression showed a strong preference for somber music, saying it made them feel calmed, soothed, and “even uplifted.”

Certain songs always make me misty-eyed, such as Tracy Chapman’s “The Promise.” When she sings the words, “I’ll find my way back to you,” she gets me every time. Photo Hans Hillewaert, Creative Commons.

Like an empathic friend, melancholy music meets us where we’re at.

And when songs make us weep or put a lump in our throat, music can trigger a cathartic release.

The late neurologist Oliver Sacks had deep appreciation for music, a passion he explored in his bestselling book Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain.

Photo Maria Popova, Creative Commons.

Music reaches at a level beyond conscious thought. More than any other artform, it is both “completely abstract and profoundly emotional,” wrote the late neurologist Oliver Sacks:

“Music can pierce the heart directly; it needs no mediation.”

Early psychiatrists had an intuitive grasp of music’s mood-enhancing effects.

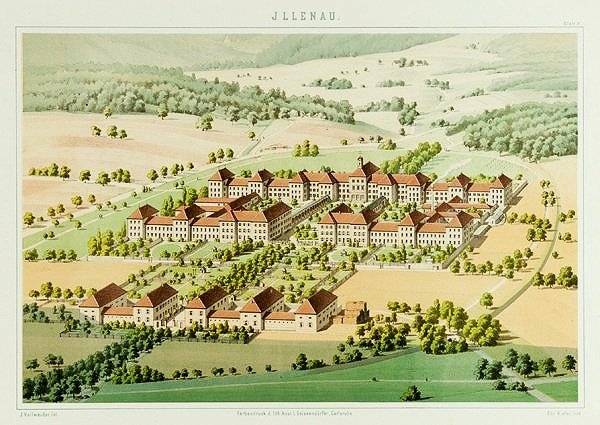

Image from a 1865 lithograph depicting the Illenau asylum in Baden, Germany, where music and nature were considered vital agents of healing in recovery from mental illness. Image U.S. public domain.

In the mid-nineteenth century, specialists in Baden, Germany, believed individuals with mental illness healed best in a pastoral setting with plenty of music— especially Mendelssohn.

The local asylum, Illenau, urged patients to sing in the choir, join the in-house band, and try writing their own musical compositions.

The structures that housed the 19th century Illenau asylum — an early adopter of music as medicine for mental illness — still stand today. Photo Gerd Eichmann, Creative Commons.

Near the turn of the 21st century, a critical mass of scientists began to shed light on the mind-boggling chemicals and electrical patterns activated by music.

At the Montreal Neurological Institute, Dr. Robert Zatorre and Valerie Salimpoor, a McGill graduate student, became the first to prove that music triggers the release of dopamine in the brain — stimulating some of the same pathways activated by chocolate, addictive behaviors and sex.

Ball-and-stick model of a dopamine molecule: gray=carbon, white=hydrogen, blue=nitrogen, red=oxygen.

Image Ben Mills, worldwide public domain.

When music builds to a peak moment during, say, a drawn-out drumroll, we get a surge of dopamine.

Then, if the climax exceeds our expectations — with, perhaps, a spectacular crash of cymbals — dopamine spikes again.

Activating the brain’s dopamine pathways, music stimulates the putamen (involved in motor movement), the nucleus accumbens (involved in pleasure), and the body’s descending analgesic response via the spinal chord. Illustration adapted from image by Patrick J. Lynch, Creative Commons.

Dopamine isn’t the only chemical involved in musical pleasure.

The brain makes its own versions of heroin, morphine, and cocaine. Known as “endogenous opioids” (“endogenous” meaning “of internal origin”), these neurochemicals give us everything from a “natural high” to a mild tranquilizing effect.

Dr. Zatorre, along with colleagues in Spain and France, theorizes that music gives us two kinds of delight: intellectual enjoyment and physical pleasure — goosebumps, chills, prickles down the spine.

Goosebumps, one of the physical pleasure responses elicited by music. Photo Ildar Sagdejev, Creative Commons.

While the roles of dopamine and endogenous opioids remain “very much under debate,” said Zatorre, he believes dopamine may be responsible for our aesthetic enjoyment of music, while our endogenous opioids enhance our physical pleasure in music.

Pleasure is life-affirming. On the flip side, a lack of pleasure in normally enjoyable things is a hallmark of mood disorders including clinical depression.

Early in our evolution, physical pleasures including sweet foods and sex helped keep us alive. But the human brain developed, we learned to find pleasure in activities that required higher-level thinking, such as basking in Brahms. Neuroscientists refer to hits of bliss from art or music as “aesthetic” or “cognitive rewards.” Photo Stefano Mortellaro, Creative Commons.

Pleasurable music can take the edge off anxiety.

The evidence comes from surgical wards, where patients with acute anxiety end up with more pain, a higher risk of infection, and longer recovery times. Although sedatives calm most patients, they also carry the risk of breathing problems, blurred vision, dizziness, and agitation.

Anesthesiologists searched for alternatives.

Artwork entitled “Anxiety” by the artist Bhargov Buragohain, Creative Commons.

In a Barcelona hospital, for example, one group of surgical patients received a standard dose of Valium. A second group listened to half an hour of classical or new-age music, both the day of the procedure and the night before.

Just before the surgeries, researchers measured patients’ blood pressure, heart rate, cortisol, and anxiety levels.

They found no difference between the two groups.

As a treatment for preoperative anxiety, the researchers concluded, music was “as effective as sedatives.”

Music dials down chronic stress, as well.

A Dutch review of 104 clinical trials concluded that listening to slow-paced music for just twenty to thirty minutes has “a direct stress-reducing effect.”

Throughout history, however, superstitious beliefs about the “power of music” have taken bizarre forms.

Page from an extensive chapter published in 1641 on “tarantella” music as an antidote to tarantula venom, from the text Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. Image scanned by Feldkurat Katz, U.S. public domain.

In the Middle Ages, fast-paced “tarantella” music was the go-to remedy for a nebulous illness that plagued the Mediterranean for several hundred years.

While tending rows of tomatoes and spicy peppers, peasants developed sudden breathing problems, melancholy, and a “sensation of dying.”

They blamed their symptoms on the venom of the European tarantula spider (although many “victims” showed no sign of spider bite). Frenetic dancing to tarantella music was the only “cure.”

I’ll bet the peasant remedy actually worked — but not as a direct antidote to spider venom.

Belief in the mysterious spider sickness gave depressed peasants a socially acceptable culprit for their miseries under feudalism. More importantly, it gave them an excuse to get out of the field ruts and join in a mood cure that put a spring in their step.

There’s even some science to back up this approach.

In a large 2017 review, German researchers noted “highly convincing” evidence that music improves symptoms of depression and quality of life.

The poet Emily Dickinson aptly described depression as “a funeral” in the brain.

Clinical depression brings persistent feelings of sadness and low self-worth, along with sleep problems, lack of energy, and in many sufferers, thoughts of suicide.

Photo Amherst College, public domain.

People with clinical depression often improve with antidepressants and talk therapy. But in a Cochrane review, music therapy offered an extra boost compared to standard treatments alone.

Of course, music therapy isn’t the same thing as moping around listening to sad cello concertos.

Depending on the condition, from brain injury to debilitating grief, people working with a certified music therapist might show improvements beyond what other treatments can offer.

When it comes to clinical depression, however, it’s unclear whether music therapy relieves symptoms any better than music listening alone.

Music-therapy session for cancer patients in Bristol, U.K.

Registered music therapists have extensive university-level training in using music to treat physical, cognitive, and emotional issues.

Photo Creative Commons.

In a study of cancer patients with low mood, music therapy and solitary listening offered similar benefits.

Some patients preferred working with a music therapist, saying they liked the feeling of camaraderie and support. But others felt anxious or even hostile when a therapist handed them an instrument or asked them to sing.

Left alone with headphones, one patient said, “You can concentrate more on your music, and it’s like it relaxes you more.”

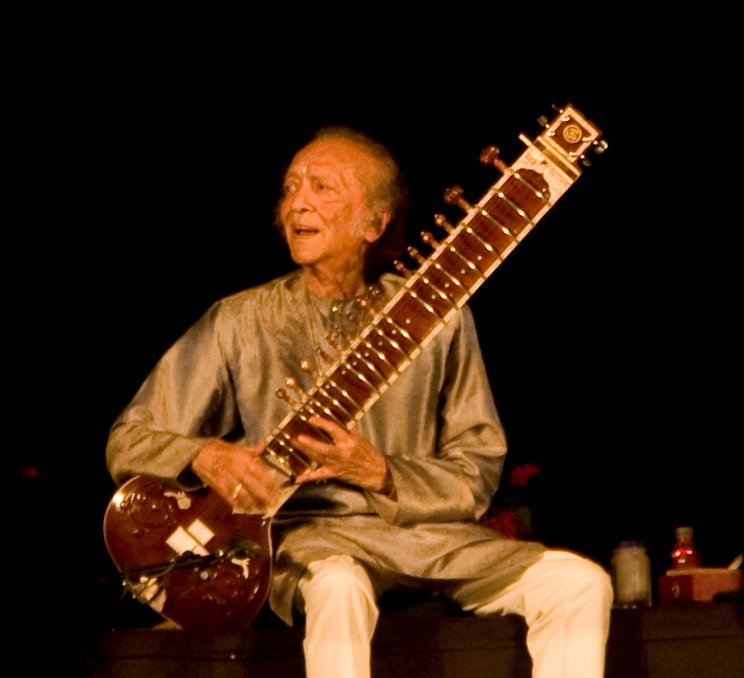

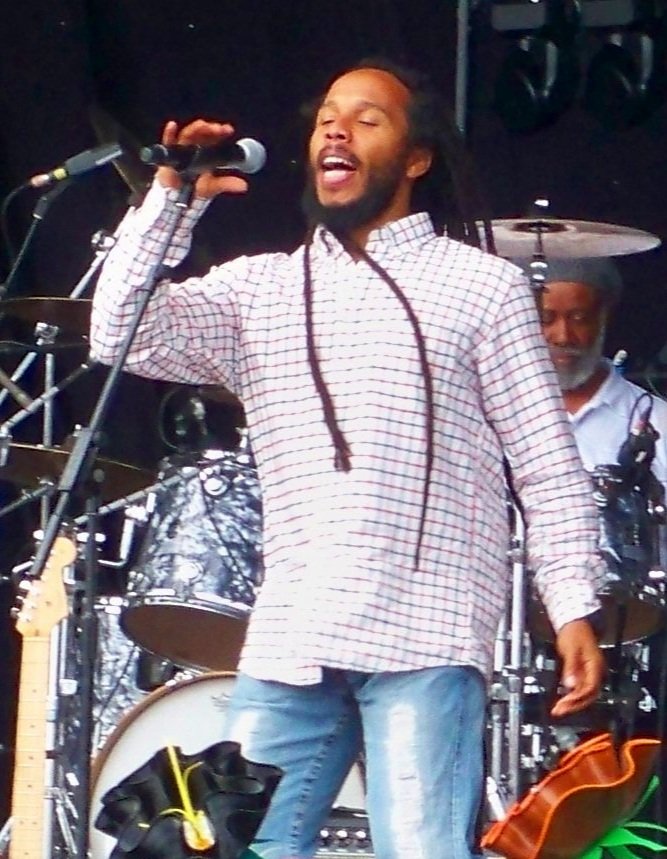

Just about any music may offer temporary relief from depression, as long as we enjoy the music. Studies have shown benefits using everything from European classical to Indian ragas, Irish folk to reggae.

Researchers in North America and Europe have described music as an “emerging treatment option” for mood disorders that “has not yet been explored to its full potential.”

Yet in many parts of the world, this aspect of music is blatantly obvious.

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk’s insightful book emphasizes treatments that address the insidious effects of trauma beneath conscious awareness. Photo Adriana Barton, all rights reserved.

Renowned psychiatrist and trauma specialist Bessel van der Kolk emphasized this point in his bestselling book The Body Keeps the Score:

“The capacity of art, music, and dance to circumvent the speechlessness that comes with terror may be one reason they are used as trauma treatments in cultures around the world.”

In recent years, Western aid organizations have made efforts to provide culturally sensitive programs.

In 2012, for example, a group called Musicians Without Borders launched Rwanda Youth Music, offering drop-in drum circles, therapeutic music sessions, and music camps for youth coping with trauma, poverty, and HIV.

Approaches like these, depending on the person, can be more helpful than talk therapy.

To quote the Danish storyteller Hans Christian Andersen, “Where words fail, music speaks.”

Musicians Without Borders (video from January 2020): Emir Hasani from the Republic of Kosovo visited Rwanda to share innovative band coaching approaches with youth in the capital city Kigali. Five bands were formed from scratch; within a week, each band wrote, recorded and performed two songs.

Delving into the neurochemistry of music helped sharpen my understanding of its powerful influence on human emotions and mood. At the same time, I had to ask myself, once again, how I became so unraveled.

If music lifts anxiety and depression by stimulating pleasure chemicals, then playing the cello day after day should have made me the picture of mental health. Instead, it drove me to burnout and despair.

Did I have a glitch in the pleasure pathway in my brain?

A conversation with Barry Bittman, an American neurologist, offered more insight.

Bittman conducted some of the first studies demonstrating that music can strengthen our immune response. But under the wrong conditions, he added, music can have the opposite effect.

Beginners playing djembes in a drum circle. Image worldwide public domain.

Bittman divided non-musicians into three groups. The first joined a drumming circle for half an hour. The second sat in a circle and listened to drumming music, while the third read newspapers and magazines.

Initially, he found no differences in their blood samples. “Not a damn thing.”

Bittman was nonplussed. Then he figured out that most of these non-musicians had either had a negative experience with music earlier in life or were convinced they weren’t musical.

Being asked to drum on the spot was stressing them out.

Bittman scrapped his approach. Next, the beginner drummers pounded out the syllables of their names, played with shakers, and jammed however they liked.

This time, participants showed a surge in natural killer cells, the specialized white blood cells that seek and destroy pathogens and cancer cells.

Given the freedom to make their own music, Bittman said, participants loosened up and embraced a spirit of fun and camaraderie.

“That’s when the magic happens.”

With these words, everything clicked. My music training was almost guaranteed to induce a stress response — enough to dampen my immune system, along with my pleasure pathway.

I loved music, loved the sound of the cello. But I almost never played with a sense of creative freedom or fun.

This realization hurt. I had done it all wrong.

Click here to view the next chapter of Wired for Music: The Visual Companion. Sign up to receive an email alert for each post.

To order the book Wired for Music, see links on this page.

Sources for all information in this post can be found in the endnotes of the hardcover and paperback editions.

Copyright note: The author is the copyright holder of all text but not all images included in this post. Every effort has been made to identify and indicate the copyright status of each image pictured. In some cases, copyrighted material has been included for the purposes of teaching and scholarship in accordance with “fair use” regulations in Section 107 of U.S. Copyright Law.

Please contact me with any questions, permissions requests, or concerns about copyright.

Disclaimer: Discussions about health topics provided in this post, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment. The author accepts no responsibility or liability for any health consequences relating to information published on this website.