A chapter-by-chapter series of photos, drawings and videos illustrating key ideas in my book Wired for Music. Click here to view the series from the start.

Chapter 2: The Music Instinct [excerpts]

My first boyfriend after I quit the cello was a brooding drummer who test-drove his songs on street corners.

I followed him and his Gretsch kit to the grimiest bars in town, thrilling to the sound of his pulsing tom-toms and bass.

My punk ex-boyfriend’s Gretsch drum kit looked similar, but far less sparkly!

Photo Drum Crew, Creative Commons.

Although some of us have stronger musical skills than others, the myth of musical talent has been largely debunked.

As the neuroscientist Daniel Levitin, author of This Is Your Brain on Music, explains, there’s no such thing as a “music gene” or a “center in the brain that Stevie Wonder has that nobody else does.”

Left: Daniel Levitin’s book “This Is Your Brain on Music” (2006) became a perennial hit. Right: Levitin, a neuroscientist, author and musician, has performed with the likes of Bobby McFerrin, Rosanne Cash and Sting.

Like other animals, humans evolved in a world thrumming with sounds — whistling winds, cawing crows, chirping squirrels, burping frogs.

Above: Eastern gray squirrel, photo Rhododendrites, Creative Commons. Cawing carrion crow, photo Marie-Lan Taÿ Pamart, Creative Commons. Marsh frog, photo Peter Trimming, Creative Commons.

Steven Pinker enraged musicologists worldwide in his 1997 book How the Mind Works, dismissing music as nothing more than “auditory cheesecake.”

Music may be a sweet treat for the ear, but dismissing it as nothing more than “auditory cheesecake” ignores its inherent role in human evolution.

Photo zingyyellow, Creative Commons.

Gary Tomlinson, a musicologist at Yale University, traced the origins of music to a time before language, before human culture — before our ancestors could conceive of a distinct self.

The building blocks of music, he wrote, helped shape the modern brain.

In the video above, Yale musicologist Gary Tomlinson explores music’s evolutionary emergence, “and the connections of musicking to language, cognitive complexity, and the metaphysical imaginary.”

As I waded through Tomlinson’s dense academic text, my thoughts drifted towards my own origins.

Then something dawned on me: without music, I might not be here at all.

From left: My yogi-mathematician father and artist mother met in the mid-1960s through a shared love of music, in the sitting room of a boarding house in Toronto.

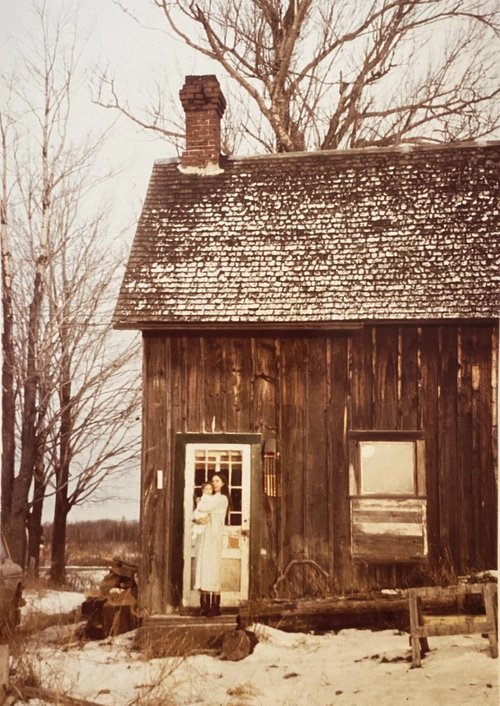

While expecting me, my parents lived in a one-room cabin in Carlsbad Springs, a rural area not far from Ottawa.

My parents owned just a handful of records in this cabin, where I came into the world during my older sister’s nap.

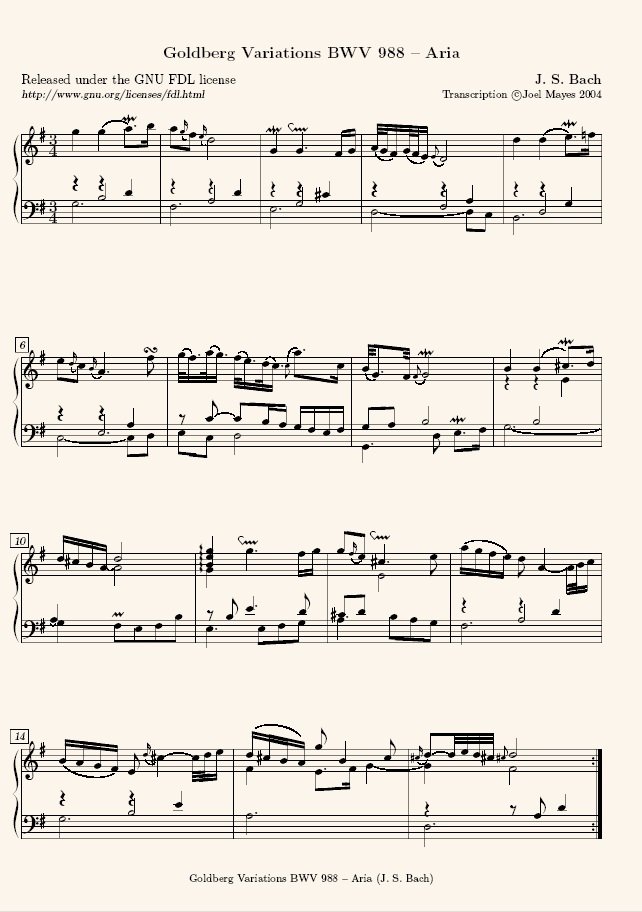

I was born — and likely conceived, my mother said — to the chiseled strains of Glenn Gould’s 1955 recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

In an EEG study, researchers concluded that in humans, the ability to perceive a musical beat is “functional at birth.”

But when researchers adapted the EEG experiment on newborns in a study of rhesus macaques (a type of monkey native to Southeast Asia), they found no sign that macaque brains could detect a musical pulse.

Based on EEG experiments, the brains of rhesus macaques do not detect a musical beat the way human newborn brains do.

Photo Charles J. Sharp, Creative Commons.

Snowball, the boogying cockatoo, was the first documented case of an untrained animal that could match a musical beat. (Snowball later hit the big time bopping to “The Piña Colada Song” in a TV ad for Taco Bell.)

Above (video): Snowball bops to the beat in the Taco Bell commercial.

In exchange for bites of herring, Ronan, a California sea lion, would bob her head up and down to the beat of a metronome and switch tempos on a dime.

Above: In this CNN video report, Ronan the sea lion grooves to the Backstreet Boys and Earth, Wind and Fire.

Musical animals give hints that the neurological underpinnings of music might be older and more broadly shared than we ever imagined.

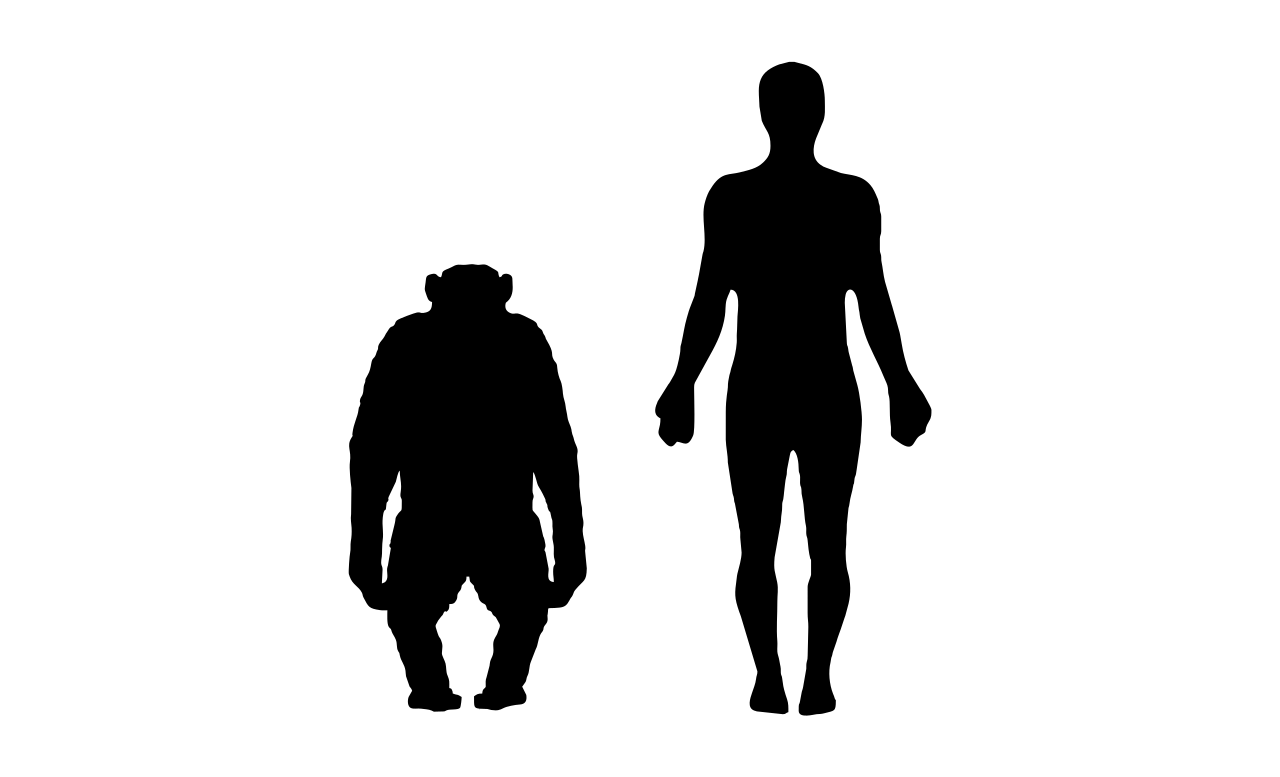

But somewhere down the line, human ancestors stumbled on ways to sharpen [our musicality] for reasons that chimps, our closest relatives, didn’t have.

Chimps and humans separated from our last common ancestor roughly six million years ago.

Illustration The Nature Box, Creative Commons.

Music, like our species, has origins in East Africa.

Along the highway between the Serengeti grasslands and Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater — a meadowy oasis teeming with lions, zebras, elephants, and wildebeest — two colossal skulls of concrete mark the turnoff to the “Cradle of Humankind.”

In Tanzania, the turnoff to the “Cradle of Humankind” — Olduvai Gorge — features six-foot-tall concrete skulls of the hominid species Paranthropus robustus and Homo habilis.

The museum at Odulvai Gorge displays a replica of the Laetoli footprints discovered in 1978 by Mary Leakey.

Replica of the Laetoli footprints discovered in Tanzania in 1978 by Mary Leakey. Photo Momotarou2012, Creative Commons.

Imprinted by feet hardly different from our own, the Laetoli trail proved that our ancestors walked upright, with a human-like stride, at least two million years before the massive growth spurt in the hominin brain.

In these footprints, Anton Killin, an evolutionary theorist, sees traces of rhythm.

But ancient neural connections leave no fossil record. They’re impossible to prove. Paleolithic tools offer more tangible clues.

Tomlinson, the Yale musicologist, believes the building blocks of music emerged from the rhythmic chipping of rock on rock. Homo erectus began chiseling diamond-shaped hand-axes about 1.7 million years ago.

Left: Lower Paleolithic hand axe, roughly 1.2 million years old, taken from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania; currently in British Museum, photo public domain. Right: Bifacial symmetrical pointed hand axe circa 280,000 BCE; photo (cropped) via Portable Antiquities Scheme, Creative Commons.

Neurons that fire together, wire together. Thus, as our ancestors sharpened stones, tool-making sharpened the brain.

Next came fire. Homo erectus learned to harness flames at least 790,000 years ago, and possibly earlier.

Nourished by roasted tubers, hippopotamus, elephant, and boar, early brains doubled in size.

For Homo erectus, fire added leisure time.

Bored and restless around the primeval hearth, they might have bonded by synchronizing their voices and body movements, said [Anton] Killin, “rehearsing” precursors of song and dance.

Prehistoric cooking fires, over centuries, fanned the flames of human imagination. Photo Alasdair, Creative Commons.

Like a moth to a flame, my mother was drawn to music and adventure. Widowed at age twenty-six by my father’s death, Mom hitched a ride from Ottawa to Vancouver with two toddlers in tow.

Within weeks, she fell in with a band of ragtag musicians.

I was in diapers when she got cozy with the Pied Piper of the group, a tall and bushy-haired Californian named Michael Fles.

Though I have no memory of this time, as a toddler, I was surrounded by jamming musicians.

In Vancouver, Michael [Fles] worked the system, applying for a government grant to fund ‘spontaneous music workshops’ for children with special needs.

He got the idea from Christopher Tree, the musical wizard he’d followed to Woodstock the year before, in the summer of 1969.

Above: Trailer from the 2018 documentary “Christopher Tree” from Les Blank Films. Tree was a direct influence on the ‘spontaneous music’ scene my mother was part of in Vancouver. In the summer of ‘69, Tree opened each day of the Woodstock festival with a cacophony of Tibetan temple gongs.

Mom followed her musician friends to the mountains of Chiapas, where she tried her hand at Mayan-style pottery.

My mom, a widow in her late 20s, playing one of her clay flutes in Mexico. I was a toddler along for the ride.

My earliest memory is of a bonfire crackling in daylight as a long line of women carry earthen pots to the flames.

Mom said this memory fits a time when I was three, in the Mayan pottery village of Amatenango del Valle.

I found this photo recently while emptying my mother’s house. Imagine my excitement — I had never seen it before! The image fits my earliest memory: women firing clay pots in the village of Amatenango del Valle. Photo Susan Feindel, all rights reserved.

We slept in an abandoned stable in Chiapas, much to the amusement of the Mayan villagers.

Gringos locos, they must have thought.

The abandoned stable in Chiapas where my mom, her boyfriend and my sister and I slept. Photo Susan Feindel, all rights reserved.

A black-and-white photo shows me in pigtails and a handwoven dress, sitting in the dirt. My chubby hands clutch a pottery flute shaped like a child with a round face and curly hair.

The clay figure is me. I am blowing into the hidden mouthpiece, filling myself with sound.

Me in Mexico at nearly three years old, playing one of my mother’s flutes (it is shaped like me).

I have no memory of playing this ocarina, or of the two musicians who inspired my mom to make flutes out of clay.

Photo Susan Feindel, all rights reserved.

Meanwhile, back in Vancouver, two members of the “children’s spontaneous music workshops” regrouped in 1976 to launch Canada’s first training program in music therapy, at Capilano College (now Capilano University).

One of the founders, Nancy McMaster, said the program never strayed from the values of spontaneity and free expression rooted in “Woodstock, the ’60s, and some hitchhikers.”

Above: Music therapist Nancy McMaster in the documentary “Celebrating the Beginnings of the First Canadian Music Therapy Program” founded at Capilano University in 1976. This film features key members of the ‘spontaneous music group’ my mom was part of when I was a toddler.

The budding music therapists encouraged children with special needs, many of them nonverbal, to tune in to their own musical impulses moment to moment, and communicate in ways that transcended words.

While their approach was radical at the time, it was hardly counterintuitive. The earliest humans — also nonverbal — might have made music much like this.

Half a million years ago, in a balmy period in southern England, Homo heidelbergensis hunted rhinoceros and megaloceros (giant deer), leaving a cache of bones and stone tools at Boxgrove in West Sussex.

In southern England, human ancestors hunted megalocerus (giant deer) that stood roughly 6’7” at the shoulder and weighed more than half a ton. Reconstruction of extinct megalocerus at the Prehistoric Park in Tarascon, France. Photo Tylwyth Eldar, Creative Commons.

To divvy up the spoils and reinforce the chains of command without a brawl, the leaders would have hollered, pounded the ground, beaten their chests.

Anatomical changes helped them make themselves clear.

These hunters had lost the air sacs around the larynx that allow other primates to ‘hoot-pant’ without hyperventilating. Without these air sacs, the Boxgrove band could vocalize with close to human finesse.

Our human ancestors lost the laryngeal air sacs (inflatable extensions of the vocal tract) that allow chimpanzees to “hoot pant” and breathe at 10 to 15 times the normal rate. The loss of laryngeal air sacs allowed humans to vocalize with greater finesse. Photo courtesy Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest.

During the last ice age, small bands of sapiens huddled in the caves of Germany’s Swabian Alps, playing flutes fashioned from mammoth ivory and vulture bone.

In this cave, Hohle Fels, in Germany’s Swabian Alps, archeologists discovered flutes dating back more than 40,000 years. Photo Dr. Eugen Lehle, Creative Commons.

These flutes look like penny whistles, with finger holes carefully spaced to play tunes in five notes, similar to the pentatonic scales found in Scottish jigs or Javanese gamelan music.

Ice-age flute made of vulture bone, discovered in Hohle Fels cave in Germany’s Swabian Alps and dated at more than 40,000 years old.

Photo Hannes Wiedmann, Creative Commons.

On a replica of the vulture-bone flute, one experimental archaeologist managed to play “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Above: Amateur archaeologist Wulf Hein plays melodies on a replica of the vulture-bone flute created during the last ice age and discovered in Germany’s Swabian Alps.

Remarkably, our auditory cortex can rewire itself to process touch as well as sound. The renowned percussionist Evelyn Glennie, profoundly deaf since age twelve, often performs shoeless to allow her feet to feel the vibrations from the floor.

The human body, she told The Globe and Mail, is “like a huge ear.”

Percussionist Evelyn Glennie, deaf since childhood, performing at the Moers Festival in 2004. Photo Creative Commons.

Most children can learn to hum in tune and dance to the beat, grinning all the while.

Anyone who doubts this can check out videos of preschoolers wiggling to music in Mexico, Cuba, or Senegal.

Above: Video of a Cuban preschooler dancing salsa in Havana.

As a fledgling journalist, I struggled to pay the bills. Besides my freelance gig writing for a Reader’s Digest coffee-table book series, I cleaned houses and worked as an extra on film sets, wearing everything from zombie makeup to a torpedo bra for the role of a ’50s waitress.

Snapshots from my days as an extra on movie sets in mid-1990s Vancouver.

I was a “background performer” on shows ranging from The X-Files to Happy Gilmor (starring Adam Sandler).

If only I’d known sooner about the deep roots of music in my early life, and in the human brain. I might have had something to hold on to in my late twenties when I tried to reinvent myself as a cellist…

Follow here to view future chapters of Wired for Music: The Visual Companion. Sign up to receive an email alert for each post.

To order the book Wired for Music, see links on this page.

Sources for all information in this post can be found in the endnotes of the hardcover and paperback editions.

Copyright note: The author is the copyright holder of all text but not all images included in this post. Every effort has been made to identify and indicate the copyright status of each image pictured. In some cases, copyrighted material has been included for the purposes of teaching and scholarship in accordance with “fair use” regulations in Section 107 of U.S. Copyright Law.

Please contact me with any questions, permissions requests, or concerns about copyright.

Disclaimer: Discussions about health topics provided in this post, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment. The author accepts no responsibility or liability for any health consequences relating to information published on this website.