Inside Ernesto Neto’s otherworldly creation in the Grand Palais

Read moreNarrating an audiobook: 7 things authors should know

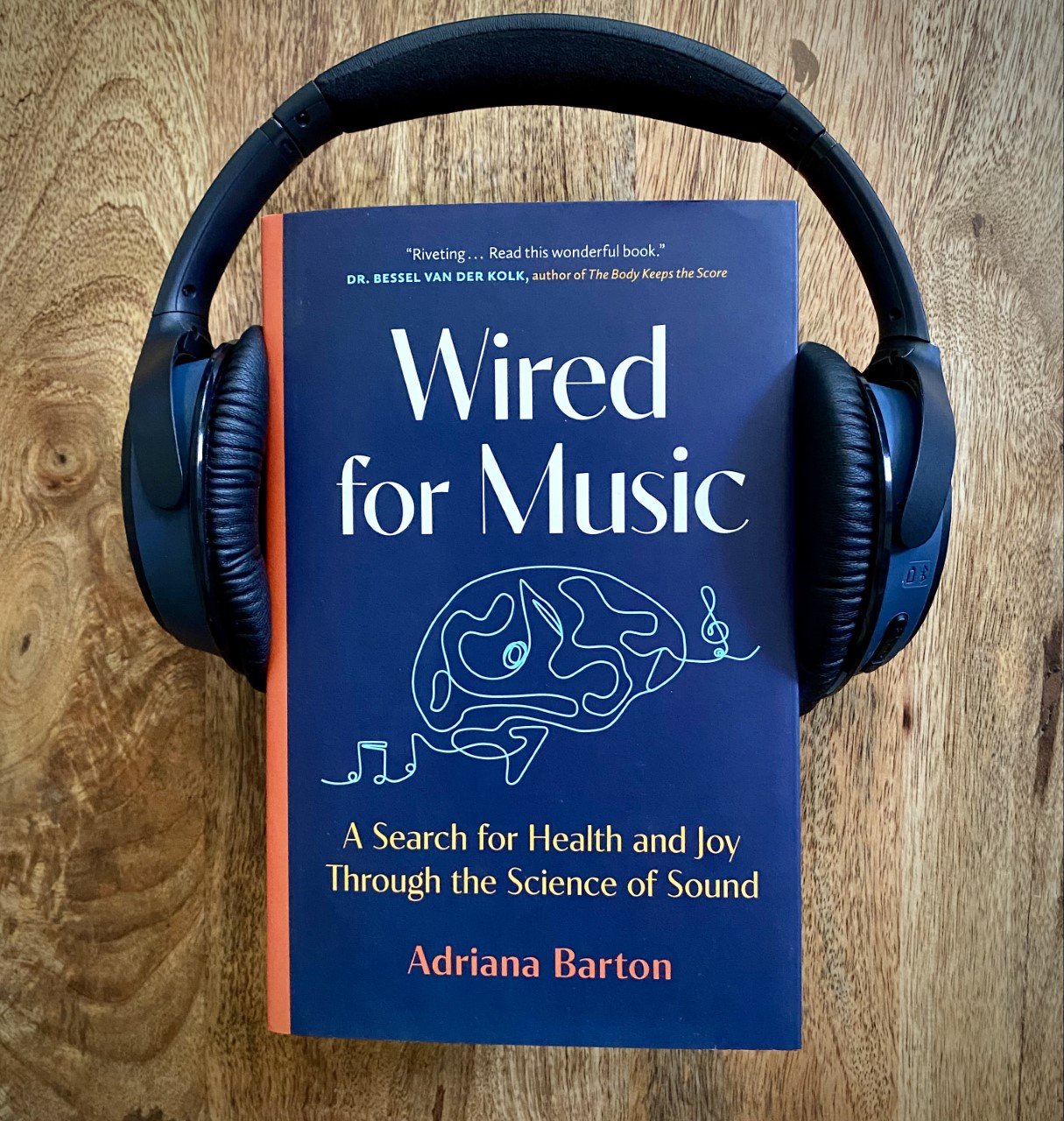

Editing my first book took so much time that I didn’t give the audiobook a moment’s thought until Wired for Music was sent to the printer.

Weeks later, I spent more than 30 hours in a recording studio narrating my science memoir. Fortunately, my publisher handled all dealings with the production company, but I had to learn how to narrate on the fly.

Here are seven things about audiobooks that authors need to know:

First day in the studio recording the audiobook version of Wired for Music; check out the giant mic and the screen scrolling the text

Don’t assume you’ll be the narrator.

Even if listeners say they prefer audiobooks narrated by the author, this preference does not apply to authors with an erratic reading pace or a monotonous voice.

Writing and narrating are very different skills — and in standard book deals, publishers buy the rights to produce (and profit from) the audiobook edition. Several authors have told me their publisher turned down their offer to narrate their own book.

I had to submit an “audition tape” to narrate mine. Using an iPhone, I recorded myself for five minutes of nonstop reading, trying to get the nuances and pacing right. (Not as easy as it sounds.)

Although my audition landed me the part, I was told to speed up my reading in the studio — I had overcorrected my fast talking pace.

It helps to listen — and read up.

To get a sense of what works and what doesn’t, I downloaded highly rated audiobooks by author-narrators such as Brené Brown (Atlas of the Heart) and James Clear (Atomic Habits). Then I listened to previews of audiobooks described by reviewers as “boring” or “annoying.” (In most cases, I had to agree.)

For practical tips, I read this article in the Guardian and this one by my former Globe and Mail colleague Marsha Lederman (author of Kiss the Red Stairs).

I learned that audiobook producers often have a director to guide the narrator (mine did not). And that voiceover artists recommend eating apples at break times and drinking hot liquids with lemon to soothe the throat. Some even spritz their throat with Chloraseptic (mine got scratchy, but never that sore).

In the studio, there’s a lot going on.

Reading from a brightly lit screen, I could hear my own voice streaming through the headphones simultaneously — along with the clicking and tapping of controls from the sound engineer in the adjacent booth.

As the pages scrolled down, I tried to anticipate how I would read each line and scan ahead for a complex sentence or tricky word. (Tip: Look up less familiar words and place names in advance on a site such as YouGlish, a handy pronunciation tool.)

The mic picks up everything.

The rustling of clothing. Stomach gurgles. A subtle shift in weight from one foot to the other. I got in the habit of wearing “low noise” clothing (leggings and a soft sweater) and eating at least an hour beforehand to keep hunger and digestive noises at bay.

You become hyper-aware of your writing choices.

I didn’t want my science memoir to be a slog to read, so I kept chiseling and chiseling at the sentence level. All that editing was a huge advantage at the audiobook stage, as I rarely found myself stumbling over my own syntax or regretting a long, back-ended sentence that didn’t flow from the previous idea.

(Many thanks to my stellar book coach, Marial Shea, who encouraged me to read early drafts to her over the phone.)

Narrating is a lot like acting.

I discovered that action verbs such as “struggled” or “pummeled” sound better if you draw them out. To make the science passages sound more like a story, I sped up in places to show my excitement in the material and slowed down in others to let a big idea sink in.

For words in quotations, I altered my voice slightly to cue the listener that they came from a different source. In memoir passages, I tried to picture the scene and remember the emotions I felt, allowing these feelings to leak into my voice.

The job is tiring, but rewarding.

For inexperienced narrators like me, audio studios budget about three hours of recording for every finished hour (my audiobook is about 9.5 hours long). Even with breaks, it takes a lot of focus to read with expression for three- to four-hour sessions, standing all the while. (Some studios give narrators the option of sitting, but standing helps keep the diaphragm open.)

To my surprise, I was not given the opportunity to listen to the full audiobook before the final edits. (I assume this is standard practice to avoid unnecessary retakes, especially with first-time narrators, who may not like the sound of their own voice.)

Even so, I enjoyed the experience. Narrating allowed me to express the thoughts I’d written in my own voice and convey the right tone for musical and scientific terms, as well as non-English words in travel scenes. I’m not sure a professional narrator would have understood their significance in the same way.

The hourly wage was a bonus, too: A typical narrator’s fee ranges from $120 per edited hour of audiobook to more than $200.

Wired for Music is available as a hardcover, e-book and audiobook (paperback to be released in Fall 2023)

My brief role as a narrator piqued my interest in the runaway popularity of audiobooks (mine is available wherever audiobooks are sold).

In 2021, audiobook sales reached $4.2-billion U.S., with a predicted growth rate of 26.5 per cent by 2030. Meanwhile, sales of print books are expected to decline or remain flat.

But as conveyers of ideas, how do the two formats stack up?

Freelance writer Markham Heid probed this question in an article for Time magazine.

Compared to audiobook listeners, he reported, book readers tend to consume information faster and retain more of it. They also save money, since paper and e-books generally cost less than audiobooks.

But audiobooks are better for multitasking — you can listen while flipping burgers or on a daily commute. And audiobook fans describe the format as a more intimate experience, especially if the author is narrating.

I’m not about to quit writing to become a full-time narrator, but this review of my audiobook made the effort feel worthwhile:

Wired for Music was moving, enlightening and somehow comforting as well. It was a wonderful weaving of personal story and science read beautifully by the author, Adriana Barton, who has a lovely voice!

Years of reading to my child must have helped. (We kept up the habit until he turned 12.)

To other authors, especially those who enjoy reading out loud, I highly recommend narrating your audiobook if you get the chance.

7 reasons to read book acknowledgments

“Thanks for mentioning me in your acknowledgments!” a friend said recently, before sheepishly admitting she hadn’t started reading my book. Did I mind? No! I often read the acknowledgments first—even if I don’t know the writer personally.

Acknowledgments offer behind-the-scenes glimpses of the writing life. As a first-time author, I’ve learned a lot from the list of thank-yous at the back of a book (including how to write them).

More than 80 names appear in the thank-yous at the back of my book “Wired for Music”—and I wish I’d included more.

From glib one-pagers to thank-the-Oscar-committee laundry lists, acknowledgements speak volumes about the author, their writing process and how the book came to be.

These pages may reveal:

Names of literary agents

How a magazine article turned into a full-length manuscript

The editor at the publishing house who took a chance on the book

Mentors, writing groups and book coaches who helped with the writing craft

Funding sources from foundations and grant institutions, and names of writers’ retreats

How the author approached book research and structure

The friends and family who cooked meals and did laundry so the author could write

Most of all, acknowledgments shed light on the tremendous effort and sheer volume of people involved in the gestation and birth of a book.

The thank-yous in my new book Wired for Music fill two-and-a-half pages—and I still didn’t fit everyone in:

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

If Rob Sanders, publisher of Greystone Books, hadn’t invited me to discuss book ideas over coffee, Wired for Music wouldn’t exist. He said my initial pitches sounded saleable enough, but then he looked me in the eye. “Do you have anything else?” I told him about my nerdy interest in music and health, and that I’d just turned down a spot in a graduate program in ethnomusicology. Then I mentioned my checkered past with the cello. His eyes brightened. “That’s the one.”

Many thanks to Greystone for publishing my first book, to editor Lucy Kenward for her structural advice, copy editor Erin Parker for her lovely manner, and editorial director Jennifer Croll, proofreader Jennifer Stewart, and text designer Belle Wuthrich for going above and beyond in the final stages.

Credit also goes to my agent extraordinaire, Martha Webb, for believing in this book through its many detours.

I am extremely grateful for friends and mentors who gave crucial feedback along the way: Angie Abdou, Dominic Ali, Susie Berg, Galya Chatterton, Sylvia Coleman, Elee Kraljii Gardiner, James Glave, Sarah Hampson, Jane Henry, Jillian Horton, Caitlin Kelly, Carol Murray, Susan Olding, Sue Robins, Gary Ross, Amy Kiara Ruth, Eric Unmacht, and Jennifer Van Evra. I owe you big-time.

Colleagues at The Globe and Mail taught me a great deal about writing and science journalism. In particular, Dakshana Bascaramurty, Zosia Bielski, Ian Brown, Wency Leung, Hayley Mick, Chris Nuttall-Smith, Paul Taylor, and Carol Toller. Sinclair Stewart approved my leave for a family gap year (sorry for taking a buyout at the end!) and Jana Pruden gave me excellent advice on structure. Early in this book project, a pivotal conversation with Marsha Lederman rescued it from the brink.

All my life I’ve been blessed to have teachers of music, formal and informal. Special thanks to Navaro Franco, David Hutchenreuther, and Alexandra Jai. A big “Obrigada!” to Kleber Magrão and other members of Brazil’s mangue scene. And as they say in Zimbabwe, “Tatenda!” to the musicians and scholars who shared their knowledge of mbira music and Chivanhu culture with me: Musekiwa Chingodza, Jonathan Goredema, Kurai Mubaiwa, Ambuya Mugwagwa, Fradreck Mujuru, Patience Munjeri, Chiedza Mutamba, Florence Mutamba, Moyo Rainos Mutamba, Alois Mutinhiri, Caution Shonhai, Joyce Warikandwa, and the lovely people at Ubuntu Learning Village. Much appreciation, too, to Erica Azim of mbira.org and Jennifer Kyker at Eastman School of Music.

As a layperson, I couldn’t have written this book without the many researchers and scientists who agreed to speak with me or review technical passages, including Bernd Brabec de Mori, University of Innsbruck; Wade Davis, National Geographic Society; Jessica Grahn, Western University; Ethan Hein, New York University; Henkjan Honing, University of Amsterdam; Mendel Kaelan, Wavepaths; Costas Karageorghis, Brunel University London; Anton Killin, Australian National University; Kevin Kirkland, Capilano University; Samuel Mehr, Harvard University; Moyo Rainos Mutamba, Ubuntu Learning Village; Andrew Newberg, Thomas Jefferson University; David J. Rothenberg, Case Western Reserve University; Michael Thaut, University of Toronto; Laurel Trainor, McMaster University; and Robert Zatorre, Montreal Neurological Institute and McGill University. (Any errors are entirely my own.)

I can’t imagine finishing a book without friends and family to commiserate with and celebrate small victories. Eternal gratitude to Ksenia Barton, Marta Becker, Galya Chatterton, Sylvia Coleman, Emily Corse, Sandrine de Finney, Jennifer Van Evra, Hal Wake, Adele Weder, and many others.

At the sentence-by-sentence level, though, no one helped more than my empathic book coach turned dear friend, Marial Shea. From the proposal stage to manuscript delivery, she was like a mother to the writer in me. (If anyone needs handholding through the writing process, hire her!)

To my way-cooler-than-me parents, Susan Feindel and Russell Barton, thank you for setting the course for an unconventional life—and for never reproaching me for quitting the cello. Your acceptance helped me heal.

To my beloved husband and son, I know it wasn’t easy living with my frazzled side in the final months of this writing project. Scott, you have supported me in every possible way, from paying the bills when I left my Globe job to believing in me when I couldn’t. I cherish you and all the joys you have brought to my life.

Finally, a big thank-you to every stranger who said they’d like to read a book like mine, from a distinguished music critic to a waiter at the Keg. Every reader is a gift.

Beyond my wildest expectations

Cover endorsements for my first book, Wired for Music, are in!

Read moreThe virtuoso girls I'll never forget

So many memories have resurfaced as I write my book. This one hit hard.

The summer I turned 15, I loaded my cello onto a bus and took a day’s journey from my hometown of Ottawa to a music academy in Charlevoix, Quebec.

Aruna Anantaraman at 15, after winning the Edythe Young Browne Trophy for top marks in violin. Photo: Courtesy Anant Anantaraman

As the bus lumbered along the St. Lawrence River, I gazed out the window, willing it to go faster. I couldn’t wait to be reunited with musicians from my youth orchestra, and maybe get pointers from an international soloist or two.

After the sweltering ride, I lugged my cello past a cluster of weathered buildings to the girls’ dormitory. I saw many familiar faces as I unpacked my things. But the bunk beds were filling up fast, with no sign of our principal violinist, or her whiz-kid sister from the second violins. Strange. Normally they’d be there.

I called out, “Where are Rupa and Aruna?”

The room froze. Everyone stared.

“Didn’t you hear?” one of the girls said at last. “They died in the Air India crash.”

The room of faces blurred before my eyes. Dazed, I shook my head. “No way,” I said. The terrorist bombing had been all over the news. But Air India Flight 182 had departed from Montreal—not Ottawa. Rupa and Aruna couldn’t have been on board.

If only that were true.

The two sisters had traveled to Montreal to catch the flight. On June 23, 1985, the bomb exploded while the passenger jet was in mid-air, sending the bodies of all 329 people—Aruna, Rupa and their mother, Bhawani, too—hurtling into the Irish Sea.

A cellist from my orchestra filled me in. “One of their violin cases was found floating in the wreck.”

Oh, God. I felt nauseous, sickened by the news. Everyone must have been talking about it for weeks. But I had kept myself scarce all summer, avoiding my expectant mom. Nine days before I left for music camp, she gave birth to a baby sister in my parents’ bedroom. I’d spent my days working for a family friend, stacking boxes in her clothing warehouse and wiping the dust off her orange tree, leaf by leaf.

I didn’t know how to explain my ignorance of the tragedy to the girls in my orchestra. While everyone else filed out for dinner, I just stood there, stunned.

I couldn’t believe I’d never see Rupa and Aruna Anantaramana again. We’d played together in the National Capital String Academy every week for more than two years.

I got the feeling she was enraptured by the music, and wanted to sweep everyone else away too.

Aruna was my age, studious and wildly talented. Music took up most of our free time, but we always smiled at each other during rehearsals. I had a soft spot for little Rupa, too. The youngest in our group, just 11 years old, she followed her big sister like a duckling.

Aruna had impeccable technique on the violin, but I never thought about the mechanics of bow strokes or hand positions when she played. I got the feeling she was enraptured by the music, and wanted to sweep everyone else away too.

Rupa was fast on her heels, displaying a talent some described as “almost Mozartian.”

Their father, Anant Anantaraman, and mother, Bhawani, came to every concert, every Saturday afternoon rehearsal. Their lives seemed to revolve around music out of sheer joy.

Music, it turned out, was the idea behind the Air India flight.

Music, it turned out, was the idea behind the Air India flight. Their mother was taking them to India to give her family a chance to hear her daughters play. Their father, a scientist in the Department of National Defence, stayed in Ottawa for work.

I could hardly imagine his horror. He lost his entire family in a flash of light.

Months went by.

The following spring, I performed in the Kiwanis Music Festival—my first competition. Shaking with nerves, I stammered my way through the Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto. Nevertheless, the judges gave me top marks, and declared me the winner of the Edythe Young Browne Trophy for strings. But where was the prize?

“Wait here,” one of the festival organizers said.

I waited so long that volunteers in the auditorium began to stack up the chairs. Then, from a far corner of the room, a man walked up to me holding a golden cup the size of a punch bowl. His eyes were sunken, and his hair was pure white. Startled, I realized he was Aruna’s father. The last time I’d seen him, his hair was black.

I stared at the hunk of gilded metal in his arms. Aruna must have won the trophy the previous year. I didn’t know what to say. He handed it to me, not saying much either. Then he gave me something else: a photo of Aruna, radiant and beautiful, holding the golden cup near her face.

I thanked him, my face burning.

Me at 16, holding Aruna’s trophy a year after I won the prize. Photo: Russell Barton

The trophy collected dust in a corner of our house for a year until it was my turn to pass it along. At the last minute, my stepfather convinced me to pose for a photo in the park down the street. “We should document this,” he said. I squinted in the sunlight, gripping the trophy with a forced smile.

I still have the photo of Aruna holding the same cup, brimming with happiness, two months before she fell from the sky.

Thirty-five years have passed since the Air India bombing, the biggest mass murder in Canada’s history. Two of the kindest, brightest girls I’ve ever known will be forever listed as victims of terrorism. This saddens me now more than ever.

During this brutal pandemic, hundreds of thousands have died—of opioid overdose, police violence, COVID-19. I cannot say their names. There are too many to remember. Instead, I’ve found myself shedding fresh tears at the thought of Aruna’s warm smile, and the little red jacket Rupa used to wear. My grief takes me aback. After all, it’s been years. But this is a cleansing pain, searing through the numbness that comes from reading so many names, on so many lists.

Aruna and Rupa’s names are engraved in the Air India Memorial in Toronto, in Humber Bay Park East. Photo: Artur / CC BY-SA https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)

Last month, I searched for news of Aruna’s father, wondering what happened to him. I read about the music scholarships he set up in his daughters’ names, and the foundation he established in honour of his wife.

Then something dawned on me: His gift to me of Aruna’s photo that day might have been a first step in making sure his family was never forgotten.

Years after the crash, Dr. Anantaraman founded a tuition-free school in southern India for children in need. The school offers hot meals and high academic standards, emphasizing the values of tolerance and peace. “I was searching for a reason to live, any little straw, any little twig, to give a point to my life,” he told a reporter.

Working with children helped him cope with the loss of his family, especially his daughters, he said.

“Aruna and Rupa, to me are still 15 and 11. They never grew up. They are just the way I saw them the last time, so beautiful, so innocent, wonderful, and talented, playing their Bach and Vivaldi.”

That’s how I will always picture them too.

In memory of Aruna and Rupa Anantaraman.

Postscript: Last month I got in touch with Dr. Anantaraman, now in his 80s, to ask his permission to publish Aruna’s photo. We hadn’t spoken since I was a teenager, and I didn’t want to add to his pain. To my relief, he welcomed my letter. In his twilight years, he wrote, hearing from a friend of his daughters brought vivid memories, and “moments of tearful joy.”

What’s the deal behind Google’s latest music Doodle?

A few days ago, Google gave its homepage a temporary logo that blew me away: This one had an earth-toned drawing of an ancient musical instrument called the mbira.

Not your basic “thumb piano”: mbira photo by Alex Weeks, Wikimedia Commons.

Outside of Africa, few people have heard of the mbira (“em-BEE-ra”). Those do often get hooked.

Last year, the American duo Pomplamoose featured a giant mbira in a breathtaking cover of the Billie Eilish song “Bury a Friend.”

I’ve been learning to play this meditative instrument for a few years now. It has a tinkling sound, like falling rain.

The mbira is made from metal keys, longer than spoon handles, fastened to a wooden slab the size of an iPad. Bottle caps give it a buzzing sound.

Caution Shonhai: mbira player and healer, February, 2019.

You need sturdy thumbs and solid rhythm to learn the intricate patterns of a traditional mbira song. The Shona people of Zimbabwe have been playing interlocking melodies on this instrument for more than 1,000 years.

Google’s Doodle nod to the mbira has Zimbabweans rejoicing worldwide. (Not all, though: some Zimbabwean scholars are calling Google’s project a form of “cultural vampirism.”)

Nevertheless, I’m glad to see people in high-tech places paying attention to other kinds of ingenuity.

I got to know the mbira better last year on a family trip to Zimbabwe. We landed in the capital city, Harare, and then made our way to the rural village of Ubuntu, named for the African philosophy that translates as “I am, because we are.”

We spent a few days hanging out with children bathed in mbira music since before they were born, along with musicians who filled us in on its fundamental role in Shona communities.

The Shona regard the mbira as a sacred instrument—a way to connect with ancestors long past. Several musicians described it to me as a “cell phone to the spirit world.”

Mbira party at Ubuntu village, 2019. From left: Joyce Warikandwa, Dzekwa Samaita, Chiedza Mutamba.

Google’s mbira Doodle barely touched on Shona spirituality (a respectful choice for a topic far too complex to cover in a brief video).

Art by Google “doodler” Helene Leroux.

Instead, the “doodlers” did a nice job of capturing the joy the mbira brings to those who hear and play it. The Google animations tell the story of a girl who learns to play the mbira at a young age and later inspires the next generation.

“We’ve tried to give people around the world a taste of a broad and deep cultural tradition that isn’t very well known outside its homeland,” said Jonathan Schneier, the Google software engineer who pitched the idea.

Schneier knew of similar instruments through his family in South Africa. Lots of people have heard of African “thumb pianos,” he said, but “I was curious, what are the origins, where did this come from?” He and his Google teammates followed the trail all the way to Zimbabwe.

They definitely did their homework. When I clicked on the “behind the scenes” video (at the bottom of this post), I recognized many names in their list of Zimbabwean consultants:

Fradreck Mujuru (centre) teaching in Berkeley, California. (I’m on the right, in red.)

There was Fradreck Mujuru, descendant of a long line of mbira players (and maker of the sweet-toned mbira I play). He has traveled to America multiple times to perform and teach in cities such as Berkeley.

Other familiar faces included Musekiwa Chingodza, a top mbira player, and Caution Shonhai, a musician and teacher I met in Zimbabwe.

Shonhai doubles as a healer in his village. Listening to the mbira calms the brain, he told me. This line of thinking is consistent with medical research on music as a treatment for acute anxiety. (I’ll be exploring the connection between music and health in my book.)

But the best reason to get into mbira music, of course, is pleasure.

“I think anyone who has had more than five minutes with the Zimbabwean mbira cannot forget the sound,” said Albert Chimedza, founder of the Mbira Centre in Harare, speaking on the Google video.

“To me, it’s a cross between water and air.”

learn more:

The non-profit MBIRA organization supports traditional Shona music through the sale of musical recordings, instructional media, and mbira instruments made by master craftspeople in Zimbabwe. MBIRA was founded by Erica Azim, who in 1974 became one of the first non-Zimbabweans to study the instrument with traditional mbira masters. She has taught mbira players worldwide. (I have taken several workshops with Erica, and can vouch for her gifts.)

5 ways to use music to soothe your anxiety

Photo credit: Kashirin Nickolai, Wikimedia Commons

LISTEN: Press play below to hear my interview with CBC Radio, Canada’s national broadcaster:

In these plague times, fears run wild. We try to laugh away our anxiety with memes of the feral hairdos we’ll sport after months away from the salon. But jokes are no match for the Invasion of the Body Snatchers unfolding before our eyes.

Huddled at home, many of us can do little but watch as an invisible pathogen overwhelms hospitals and threatens to sicken the people we love. As fresh horrors flash across our screens, some of us can no longer bear to look. “Today I felt like I couldn’t catch my breath,” said a friend on Facebook. She wasn’t coming down with the virus, she realized: “I was having an anxiety attack from reading the news.”

Anyone longing for a Xanax right now is not alone, because this virus not only infects throats and lungs—it’s tightening its grip on our hearts and minds. In a survey of 1,055 Americans, 41 per cent singled out anxiety as a major pandemic concern.

Music can help.

For weeks, I’ve been combing through stacks of research on music and anxiety for my book on music and health. Here’s what I found: In studies of people about to undergo invasive procedures, such as open-heart surgery, music calmed patients as effectively as Valium and other benzodiazepine drugs. Without the side effects.

“Music calmed surgical patients as well as Valium and other benzodiazepine drugs, without the side effects”

Too good to be true? Not according to the Cochrane network, a global authority on evidence-based medicine. After conducting four stringent reviews of music for acute anxiety, Cochrane gave music thumbs-up.

In this age of contagion, people worldwide have turned to music. We rejoiced at the balcony singers of Florence, Siena and Milan, whose plucky faces and dented pots and pans were so very charming, so Italian. Many of us told ourselves that if they could summon beauty and grace amid devastating loss, then maybe we could too.

Even if we’ve never touched a musical instrument in our lives, recent findings from neuroscience can help us tap into music’s stress-reducing effects. Here are five evidence-based listening tips:

1. Choose the music you love most. The more you light up the pleasure and reward system in your brain, the more music activates the same pathways stimulated by morphine and cocaine (but to a safer, milder degree).

2. Try music at 60 to 80 beats per minutes, the pace of a resting heart. Brain areas involved in regulating heart rate and breathing tend to synchronize with the tempo we hear. In a large 2019 review, slow-paced music was the most effective in lowering stress. (Playlists organized by beats per minute are easy to find online.)

3. Listen for 20 to 30 minutes. That’s the typical duration used in studies of music’s sedative effects.

4. Close your eyes and do nothing else. Multitasking increases production of cortisol and adrenaline, driving up stress.

5. Pick a sad song to make it better. Sad songs tend to move us more than happy songs, offering a cathartic release of tension, and feelings of relief.

In this pandemic, there’s no shortage of glorious music to choose from. Cellist Yo-Yo Ma has serenaded healthcare workers in a series of videos posted under #songsofcomfort. Neil Young reached out to fans with a fireside session in his home. Many other artists, from James Taylor to Jann Arden, have given online performances to lift our spirits.

Amateurs, too, are sharing their music. Martha Smith of Florida posted a video for her 76th birthday of herself playing “Solace” by Scott Joplin, king of ragtime. “Despite mistakes,” she wrote on YouTube, “I kept going, as we all must.”

(P.S. The tips above are for mild to moderate anxiety and stress. If you have moderate to severe anxiety or stress, please seek professional help.)

Disclaimer: Discussions about health topics provided in this blog, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment. The author accepts no responsibility or liability for any health consequences relating to information published on this blog.

‘Binaural beats’ debunked: These apps offer cool marketing, but iffy health effects

Optical illusions mess with how we see things. “Binaural beats,” a type of auditory illusion, mess with how we hear things—and may play tricks in other ways, too.

Photo credit: Darekm135 / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

An odd thing happens when you listen through headphones to two steady tones at slightly different frequencies, one in each ear. You start to hear a low beat that sounds like it’s coming from inside your head. But this third sound is just a figment of your brain’s auditory system. A phantom pulse.

What’s up with that? Scientists have known for decades that our brainwaves tend to synchronize, or “entrain,” with the rhythms we hear. In theory, slightly mismatched tones may confuse the brain. If one ear picks up a tone at 550 Hertz, while the other hears 558 Hertz, the brain will perceive a third frequency—binaural beats—at the points where the sine waves bump together.

Researchers haven’t fully studied binaural beats, let alone the possible health effects. But that hasn’t stopped an overkill of apps from marketing them as “digital drugs” with the power to relieve migraines, sharpen mental focus and blast away stress.

Even Bayer, maker of Aspirin, promotes binaural beats as “good vibes” for relaxation on its Austrian website.

So far, however, the evidence of any health benefits is thin.

So far, the evidence of any health benefits from binaural beats is thin

The latest study to poke holes in the hype comes from an international team led by scientists at the Montreal-based Laboratory for Brain, Music and Sound Research.

In the study, published this week in eNeuro, healthy adults wore head caps with electrodes for monitoring brainwaves using electroencephalography (EEG).

First, they listened to a series of binaural beat frequencies. Next, the same volunteers listened to frequencies mixed on a computer to create a third beat before the sound reached the ears. In this case, the third beat was part of the audio mix (and not an illusion).

After each session, the listeners rated their levels of mental relaxation, alertness and feelings of absorption in the experience.

The researchers found that binaural beats did entrain the brain—but not as much as the premixed beats. What’s more, neither had any effect on mood. A previous study, published in 2017, reached similar conclusions.

This didn’t surprise me. The mood-boosting effects of music, based on a large body of research, stem from the brain’s pleasure and reward response to our favorite sounds. Binaural beat apps use computer-generated frequencies, many of which sound only vaguely like music.

The Montreal study, to be fair, involved just 16 participants and listening sessions of eight minutes each. Chances are this study won’t put the nail in the coffin for binaural-beat diehards.

Whether binaural beats can cause a “high” remains debatable, but the power of suggestion can be intense

Digital drugs have a cult following online. Teens have posted YouTube videos of themselves “getting high” on audio tracks. Reviewers on iDoser’s website have raved about the trippy experiences they’ve had. Whether binaural beats can cause a “high” remains debatable, but the power of suggestion can be intense.

And some studies have shown possible benefits. A 2018 analysis of 22 studies concluded that binaural beats may help lower anxiety and offer modest pain relief.

Behavioral studies, however, tend to search for specific effects, such as relaxation. This approach can bias the results, noted Joydeep Bhattacharya, a cognitive psychologist who has studied the neuroscience of music. Binaural beats, he said, in an interview with Discover magazine, “raise a lot of flags.”

The few studies that have used brain imaging to understand what’s happening during binaural beats have produced inconclusive results, he pointed out. “That gives you a good indication that the story is more complicated than many of the behavioral studies want to convince you.”

Until more research is done, our best bet might be to see this phenomenon as a quirk of our gray matter—a bit of mischief from the proverbial ghost in the machine.

Disclaimer: Discussions about health topics provided in this blog, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment. The author accepts no responsibility or liability for any health consequences relating to information published on this blog.

The secret behind fast-paced music, AKA the “legal performance enhancing drug”

You’ll never find a silent spin class—let alone Zumba. Fitness instructors intuitively know that peppy music puts a spring in our step.

Now we have science to prove it.

Is music giving her the edge? Runner with headphones at Marathon Rotterdam 2015. Photo credit: Peter van der Sluijs, Wikimedia Commons

In a new study in Frontiers in Psychology, fast-paced music made exercise easier—and helped women work up a sweat.

For the study, a small group of volunteers exercised either in silence, or to pop music at three different tempos: 90 to 110 beats per minute (bpm), 130 to 150 bpm, or 170 to 190 bpm.

Some of the women walked on a treadmill, while others did leg presses. During each session, sport scientists recorded the women’s heart rates and asked them to report how much effort their workouts required.

“Listening to high-tempo music while exercising resulted in the highest heart rate and lowest perceived exertion”

After crunching the numbers, the researchers noticed a trend:

“Listening to high-tempo music while exercising resulted in the highest heart rate and lowest perceived exertion,” said Luca P. Ardigò, a sport scientist at the University of Verona, Italy.

The effect was greatest for women on treadmills, compared to those using weights. The takeaway: Exercisers doing endurance activities, such as walking or running, may get the biggest bang from upbeat music.

The study’s sample size was tiny—19 women total—and didn’t include men. Nevertheless, the findings echoed a recent systematic review from the University of Southern Queensland in Australia.

The Australian researchers combed through 139 studies on music in exercise and sport—in both men and women—and came up with four key findings:

Music makes exercise more enjoyable

Music reduces perceived effort

Music improves physical performance

Music increases blood flow and reduces the oxygen intake needed to exercise at the same intensity without music

“No one would be surprised that music helps people feel more positive during exercise,” said Peter Terry, dean of graduate research and innovation at the University of Southern Queensland. But, he added in a news release, “the fact that music provided a significant boost to performance would surprise some people.”

Faster music—at least 120 beats per minute—offered more benefits than slower music

Like the Italian study, Terry and colleagues found that faster music—at least 120 beats per minute—offered more benefits than slower music.

What’s more, exercising to the beat offered the greatest gains.

Music has been described as a “legal performance enhancing drug.”

How could this be? Human brainwaves tend to synchronize with any steady tempo we hear, including brain regions involved in core functions such as heart rate, breathing and blood pressure.

Tunes for training: author Costas Karageorghis, professor of sport and exercise psychology at Brunel University London, explores evidence-based practices in his 2016 book

So, if you want a leg up in your next triathlon or 10K, try listening to fast-paced tunes. But first, check the rules: Some competitions discourage, or even ban, the use of portable music devices for safety and performance reasons. The Boston Marathon allows headsets, “except for those participants who declare themselves eligible for prize money.”

Playlists arranged by tempo are easy to find. (A 120 bpm playlist on Spotify kicks off with the Glee favorite, “Don’t Stop Believin’.”)

Just don’t crank up the volume. Noise levels at indoor cycling studios often reach 100 decibels or more—enough, with repeat exposure, to cause long-term hearing loss.

Wear earplugs, ask the gym to turn the music down (or take your business elsewhere).

Disclaimer: Discussions about health topics provided in this blog, or in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice, nor is the information a substitute for professional medical expertise or treatment. The author accepts no responsibility or liability for any health consequences relating to information published on this blog.

One of the masterminds behind the Italian Renaissance was a mystical musician dubbed the “second Orpheus”

Household names like Leonardo da Vinci get all the credit for sparking the 15th-century explosion of art and science. But there’s more to the story.

One of the masterminds behind the Italian Renaissance was neither a painter, nor a wealthy Medici, but a depressive priest who self-medicated with music.

Without this enigmatic figure, named Marsilio Ficino, we might not have Botticelli’s “Primavera” or “The Birth of Venus.”

Sandro Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus,” painted in 1483-1483, explores classical themes championed by Marsilio Ficino. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), shown in a fresco painted by Domenico Ghirlandaio in the Tornabuoni Chapel, church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence

I stumbled across Ficino while doing research for my book.

Born in 1433, Ficino was a frail man with pensive eyes and a humped back. But Florentine intellectuals learned not to judge him by his looks, for he had the mind of a genius and the voice of a demigod. They called him the second Orpheus.

Ficino had a gift for reading Greek, at a time when ancient philosophy was making a comeback. He was the first to translate Plato’s entire works into Latin, making them available to a wide audience through Gutenberg’s new printing press.

Ficino coined the term “Platonic love”—bosom buddies without benefits—and revived core ideas from the ancient world. Before his death in 1499, Ficino became one of the most influential scholars in all of Europe.

It helped to have friends in high places. Ficino had the ear and financial backing of Cosimo de’ Medici, titan of the powerful Medici dynasty. Later, Ficino became chief tutor to Cosimo’s grandson, Lorenzo de’ Medici.

Trained by Ficino to appreciate the arts, Lorenzo supported master painters such as Sandro Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci. He even invited the young Michelangelo to live with his family at the Palazzo Medici.

Scene of Ficino’s entourage celebrating neo-Platonic wisdom around a bust of Plato. Oil on canvas entitled, “The Parental of Plato,” by Antonio Puccinelli (1822-1897). Here, “parental” means “influence.” Photo: https://villegiardinimedicei.it/villa-di-careggi/

Scholars have argued that Ficino, more than anyone else, summoned the return to beauty in the Italian Renaissance

Together, they mingled in a circle of poets and intellectuals led by Ficino. Themes from Greek and Roman mythology, championed by Ficino, appeared in the masterpieces of Michelangelo and Botticelli.

Did Ficino have a direct hand in their work? No one knows for sure. But Ficino tended to rhapsodize about Venus, describing her as a transformative force for the human soul. The voluptuous goddess became the central figure in Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus,” as well as “Primavera.”

That’s not all.

Ficino was the New Age guru of his day. A trained physician, vegetarian and ordained priest, he melded Catholicism and Greek philosophy with a dash of pagan ritual.

His mystical teachings drew artists and scientists from miles around to a sprawling estate in the hills outside Florence. In a castle-like villa that still stands at Careggi, Ficino headed a centre of learning modelled after Plato’s ancient Academy.

Set in a garden of orange and olive trees, this Medici villa doubled as a healing retreat, specializing in Ficino’s esoteric music therapy. (Today, we’d call it “woo-woo.”)

Villa Medici at Careggi, Florence. Site of the neo-Platonic Academy headed by Marsilio Ficino, who died here in 1499. Photo credit: I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7430861

An enchanting male voice beckoned visitors to an inner chamber perfumed with frankincense.

There, seated near a bust of Plato, Ficino would strum a lyre (a U-shaped harp) while singing the Orphic Hymns—sacred texts uncovered in Constantinople (Istanbul).

Modern historians have dated these texts to around the start of Common Era. But Ficino believed them to be magical incantations penned by the demigod Orpheus himself.

In the famous Greek myth, Orpheus poured his anguish into his lyre after losing his bride, Eurydice, to a fatal snake bite. Hades, King of the Underworld, was so touched by the grief-stricken songs that he allowed Orpheus to return his wife to the world of the living, on one condition: he must walk in front of her and not look back. But Orpheus snuck a peek and lost Eurydice forever.

Ficino, taking cues from the Greeks, regarded illness as a form of discord between the soul and the heavens. Like Plato before him, he saw music as the ticket to inner harmony.

For patients with low moods, Ficino recommended melodies that evoked the mellow or upbeat planets: Venus was soft and yielding. Mercury vigorous and gay. With practice, Ficino said, music could open one’s spirit to the gifts freely offered by the heavens.

“We play the lyre,” Ficino wrote, “precisely to avoid becoming unstrung.”

Bust of Marsilio Ficino by Andrea Ferrucci, in the Cathedral of Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ficino himself suffered bouts of depression. “We play the lyre,” he wrote, “precisely to avoid becoming unstrung.”

(Numerous studies have shown that music really does improve depressive symptoms. But astrology has nothing to do with it.)

Ficino’s unique blend of music, mysticism and medicine captivated Italy’s brightest minds

Ficino’s unique blend of music, mysticism and medicine captivated Italy’s brightest minds for decades. After centuries of dogma about inescapable sin, Ficino offered something fresh: a sensuous Catholicism in which art, music, fragrances and original thought ignited love in the human soul, amplifying love for God.

Scholars have argued that Ficino, more than anyone else, summoned the return to beauty in the Italian Renaissance.

But the tides turned.

At age 64, Ficino saw Dominican friar Savonarola’s “bonfire of the vanities” destroy thousands of exquisite costumes, books, artworks and musical instruments.

In this assault on beauty, wrote Ficino scholar Angela Voss, “the brilliant vision of Florentine Platonism itself was hurled into the depths of Hades by the forces of ignorance and fear.”

Ficino died two years later. His fascination for the mythical past fell out of fashion. And his heavenly voice—unlike Botticelli’s paintings—was forever lost.

Sources

Biographical details and scholarly achievements:

Celenza, Christopher S., "Marsilio Ficino", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/ficino/>.

Description of Ficino’s physique and inner sanctum at Careggi:

Walker, D.P. Spiritual and Demonic Magic: From Ficino to Campanella. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000.

Ficino’s influence on Renaissance art and philosophy:

Michael J. B. Allen and Valery Rees, eds., with Martin Davies. Marsilio Ficino: His Theology, His Philosophy, His Legacy. Leiden and Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2002.

Snow-Smith, J. The Primavera of Sandro Botticelli: A Neoplatonic Interpretation. New York: Peter Lang Inc., 1993.

Kristeller, P. The Philosophy of Marsilio Ficino. New York: Columbia University Press, 1943.

Also see writings of the late Clement Salaman, editor of a 7-volume translation of the letters of Marsilio Ficino (previously unpublished in English).

Ficino’s Renaissance music therapy and Orpheus nickname:

Voss, Angela. “Marsilio Ficino, the Second Orpheus.” In Music as Medicine: The History of Music Therapy Since Antiquity, edited by Peregrine Horden, 154-172. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000.

Ammann, Peter. “Music and Melancholy: Marsilio Ficino’s Archetypal Music Therapy.” In Florence 98, Destruction and Creation: Personal and Cultural Transformations: Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Congress for Analytical Psychology, edited by Mary Ann Mattoon, 118-129. Daimon, 1999.

Source of “Florentine Platonism hurled into the depths of Hades” quote:

Voss, Angela. “Orpheus Redivivus: The Musical Magic of Marsilio Ficino.” In Marsilio Ficino: His Theology, His Philosophy, His Legacy, edited by Michael J. B. Allen and Valery Rees, with Martin Davies, 227-241. Leiden and Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2002.

Many have stories of artist Gordon Smith's famous generosity. Here's mine.

I met Gordon Smith for the first time on a tour of his West Vancouver home, set on a craggy slope overlooking the steely Pacific.

Gordon Smith at 90, in his West Vancouver studio. The B.C.-based painter and philanthropist died on January 18, 2020, at age 100. To the right is the chair that inspired the artwork he gave me. Photo: courtesy Martin Tessler

Smith’s studio was the tidiest I’d ever seen. White walls, white floor, with nary a scuff mark or paint splatter. A trolley held brushes and jars of pigments arranged in rows. Other materials, from staple guns to canvas, were stowed behind closet doors, out of sight.

“Amazing,” I thought. Detritus from the creative process, cleaned up after the fact? (My mother’s studio never looked like that.)

But I could see why Smith kept his work space shipshape. The room itself was a work of art—part of an architectural masterpiece designed in 1964 for Smith and his wife, Marion, by their friend, Arthur Erickson.

Smith died in this home last week, at age 100.

Over the course of his triple-digit life, he earned many accolades, including the Governor General’s Award for visual and media arts.

But beyond his glorious paintings, Smith’s support for future generations may prove to be his greatest legacy.

Beyond his glorious paintings, Smith’s support for future generations may be his greatest legacy

The Smiths never had children. Instead, they dedicated much of their resources to art education. Smith worked hands-on with children through Artists for Kids, an organization that later expanded into The Gordon and Marion Smith Foundation for Young Artists.

Smith was a spry octogenarian when he showed me his house. Arranged around a concrete courtyard, this Erickson marvel of window-wrapped geometry won the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada’s Prix du XXe siècle for “enduring excellence of nationally significant architecture.”

Smith’s studio had high ceilings and oodles of natural light. The room’s footprint was on the small side, but Smith found a spot for the things he loved most. The paintbrushes of his mentor, Lawren Harris, dangled from a wooden beam.

At the side of the studio, a wrought-iron chair caught my eye. Its curvy design seemed out of place next to the Smiths’ modernist furnishings. “I rescued it from an old ice cream parlor at UBC,” Smith explained, referring to the university where he used to teach.

Chair crafted from the wire of a champagne stopper by my friend, Andrée Pouliot

I told him I’d seen a similar chair in miniature. A family friend crafted them with pliers, using the wire from stoppers of champagne.

The next day, I sent one of these tiny chairs to Smith as a thank-you for the tour. I thought he’d get a kick out of it. He did.

Writing by email, he invited me to the opening of his next exhibition. “I have something for you,” he added mysteriously.

I didn’t expect him to remember me at the crowded opening. But when I paid my respects, he told me to wait a moment. He reappeared with a cardboard tube in his hand and a twinkle in his eye.

Inside was a large etching entitled, “Chair and Bag,” signed Gordon Smith.

I chuckled. Smith had one-upped me in the furniture exchange.

(Staff reporters are not allowed to accept gifts, but I was a freelancer back then and not working as a critic.)

Over the years, I spotted Smith’s artworks in the homes of many journalist friends. This didn’t make his gift any less special. On the contrary, I felt part of a larger Smith circle of kindness.

His art touched me in other ways, too.

In 2004, I had an assignment to write about a new art collection at Four Seasons Whistler. Suspended in the grand stairwell was the showstopper: “Spring Thaw,” by Gordon Smith. At 10 by 18 feet, this acrylic on canvas was his largest creation.

I must have gazed at this immersive snowscape for half an hour before climbing the stairs to my room. The next day, the wonderful man accompanying me popped the question. We’ve been married for 15 years now.

Smith’s chair hangs in our kitchen across from the stove, next to a wily fox painted by our son when he was 5. I have a feeling Smith would approve.

“Chair and Bag,” by the late Gordon Smith, hanging in my kitchen next to a fox painted by my son at age 5

Music to cope with cognitive decline

There’s a lot of talk right now about music and Alzheimer’s. Especially in the wake of Alive Inside, the 2014 Sundance hit about nursing home residents who “wake up” after a social worker gives them headphones to listen to Schubert or the Shirelles.

But it seems we're just beginning to tap into music’s potential to help people with cognitive decline.

I wrote a Globe piece last week about a new choir in Victoria, B.C., which teams up people with dementia, their caregivers and high school students. Researchers behind the project, called Voices in Motion, are studying whether singing in a choir can reduce depression, loneliness and stigma, and improve mental functioning.

This isn't just a “fill out a questionnaire and tell us how you feel” study. Choir members with dementia, as well as their caregivers, consented to monthly tests to measure their emotional states, cognition and physiological markers such as gait and grip strength.

In the study’s pilot phase, the researchers found a lowering of depression in choir participants, and a slight bump in their mental functioning.

Music isn’t a silver bullet. It cannot cure, reverse or halt the mental decline that comes with Alzheimer’s. But here’s what singing in a choir can do:

Combat loneliness, at a chemical level: Singing with others increases levels of oxytocin, the “cuddle hormone” that gives us warm fuzzies and makes us feel less alone. Loneliness is so harmful to overall health that researchers are calling it “the new smoking” – equivalent to sucking back 15 cigarettes a day.

Harness memory centres undamaged by dementia: Memory isn’t just a matter of recalling what we ate for breakfast, or where we left the keys. We also have semantic memory (general knowledge of the world), procedural memory (the skill to remember motor tasks such as riding a bike), emotional memory and other kinds stored in different parts of the brain. Music recruits multiple memory centres at once, allowing choir members with dementia to recall new songs one week to the next.

Improve mood, and possibly mental functioning: Singing or listening to music stimulates the brain’s pleasure centres. Enhancing mood reduces depression, freeing up valuable brain resources, according to the researchers behind the Victoria choir. Choir members in the pilot study showed slight improvements in their ability to remember words from a list. They had the same brain damage from dementia, researchers said, but got more mileage from cognitive resources they had.

Dr. Stuart MacDonald, a University of Victoria psychologist involved in the study, described music a “super stimulant” for the brain.

And unlike dodgy "brain supplements" sold online, music is cheap, enjoyable and side-effect free.

Behind the scenes of my latest Globe and Mail article

I'm just wrapping up my biggest ever story for The Globe and Mail – a week before going on book leave for a year with my family in France. Normally I'd be packing by now. Murphy's law, right?

I'm not complaining, though.

Hilary Jordan and her son, Mark, a month after her husband's accident in 1987. Photo courtesy Hilary Jordan

It's been a privilege to dive into the story of Ian Jordan, the Victoria police officer who spent 30 years in a mostly unresponsive state following a car accident on September 22, 1987.

Heart-wrenching, too. His wife, Hilary Jordan, spent hours with me describing what it's like to care for someone who has only fleeting moments of awareness.

From the time their son was 16 months old to their 45th wedding anniversary in the hospital this spring, she did everything possible to give her brain-injured husband the best possible quality of life.

I visited the hospital room in Victoria, B.C., where Ian Jordan spent 15 of his 30 years in care. I met a healthcare aide who helped look after his daily needs for 27 years. I spoke with Ole Jorgensen, the Victoria constable who suffered devastating PTSD after his vehicle crashed into Jordan's police cruiser that fateful night.

Finally, I had a phone interview with Hilary's son, Mark Jordan, now 32. He can't remember a time when his father could walk or talk.

But this injured police officer’s life is far more than a movie-of-the-week tearjerker. Ian Jordan’s story ties in to the evolving science of consciousness.

Scientists are still cracking the code of human consciousness.

Medical understanding of the human brain has come a long way since 1987. Cutting-edge diagnostic tools have revealed that many patients thought to be unaware are more conscious than we think. Which brings me to the story scoop.

Ian Jordan had two music therapists. What could they do for someone who was barely conscious?

I can’t say more without revealing the story’s clincher. Check here to read more.

I'm off to pack.